- Format and manipulate large datasets

- Automate repetitive tasks using pipes and functions

- Synthesise information from different databases

- Download occurrence data through

R - Create beautiful and informative figure panels

The goal of this tutorial is to advance skills in working efficiently with data from different sources, in particular in synthesising information, formatting datasets for analyses and visualising the results. It’s an exciting world full of data out there, but putting it all together can eat up lots of time. There are many tasks that can be automated and done in a more efficient way - tidyverse to the rescue! As with most things in R, there are different ways to achieve the same tasks. Here, we will focus on ways using packages from the tidyverse collection and a few extras, which together can streamline data synthesis and visualisation!

This tutorial was developed for the Coding Club workshop at the University of Oxford with the support of the SalGo Population Ecology Team.

All the files you need to complete this tutorial can be downloaded from this repository. Click on Clone/Download/Download ZIP and unzip the folder, or clone the repository to your own GitHub account.

1. Format and manipulate large datasets

Across the tutorial, we will focus on how to efficiently format, manipulate and visualise large datasets. We will use the tidyr and dplyr packages to clean up data frames and calculate new variables. We will use the broom and purr packages to make the modelling of thousands of population trends more efficient. We will use the ggplot2 package to make graphs, maps of occurrence records, and to visualise ppulation trends and then we will arrange all of our graphs together using the gridExtra package.

We will be working with bird population data (abundance over time) from the Living Planet Database, bird trait data from the Elton Database, and emu occurrence data from the Global Biodiversity Information Facility, all of which are publicly available datasets.

First, we will format the bird population data, calculate a few summary variables and explore which countries have the most population time-series and what is their average duration.

Make sure you have set the working directory to where you saved your files.

Here are the packages we need. Note that not all tidyverse packages load automatically with library(tidyverse) - only the core ones do, so you need to load broom separately. If you don’t have some of the packages installed, you can install them using ìnstall.packages("package-name"). One of the packages is only available on GitHub, so you can use install_github() to install it. In general, if you ever have troubles installing packages from CRAN (that’s where packages come from by default when using install.packages()), you can try googling the package name and “github” and installing it from its GitHub repo, sometimes that works!

# Libraries

library(tidyverse)

library(broom)

library(wesanderson)

library(ggthemes)

library(ggalt)

library(ggrepel)

library(rgbif)

library(CoordinateCleaner)

# devtools::install_github("wilkox/treemapify")

library(treemapify)

library(gridExtra)

If you’ve ever tried to perfect your ggplot2 graphs, you might have noticed that the lines starting with theme() quickly pile up: you adjust the font size of the axes and the labels, the position of the title, the background colour of the plot, you remove the grid lines in the background, etc. And then you have to do the same for the next plot, which really increases the amount of code you use. Here is a simple solution: create a customised theme that combines all the theme() elements you want and apply it to your graphs to make things easier and increase consistency. You can include as many elements in your theme as you want, as long as they don’t contradict one another and then when you apply your theme to a graph, only the relevant elements will be considered - e.g. for our graphs we won’t need to use legend.position, but it’s fine to keep it in the theme in case any future graphs we apply it to do have the need for legends.

# Setting a custom ggplot2 function ---

# This function makes a pretty ggplot theme

# This function takes no arguments!

theme_clean <- function(){

theme_bw() +

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(size = 14),

axis.text.y = element_text(size = 14),

axis.title.x = element_text(size = 14, face = "plain"),

axis.title.y = element_text(size = 14, face = "plain"),

panel.grid.major.x = element_blank(),

panel.grid.minor.x = element_blank(),

panel.grid.minor.y = element_blank(),

panel.grid.major.y = element_blank(),

plot.margin = unit(c(0.5, 0.5, 0.5, 0.5), units = , "cm"),

plot.title = element_text(size = 15, vjust = 1, hjust = 0.5),

legend.text = element_text(size = 12, face = "italic"),

legend.title = element_blank(),

legend.position = c(0.5, 0.8))

}

Load population trend data

Now we’re ready to load in the data!

bird_pops <- read.csv("bird_pops.csv")

bird_traits <- read.csv("elton_birds.csv")

We can check out what the data look like now, either by clicking on the objects name on the right in the list in your working environment, or by running View(bird_pops) in the console.

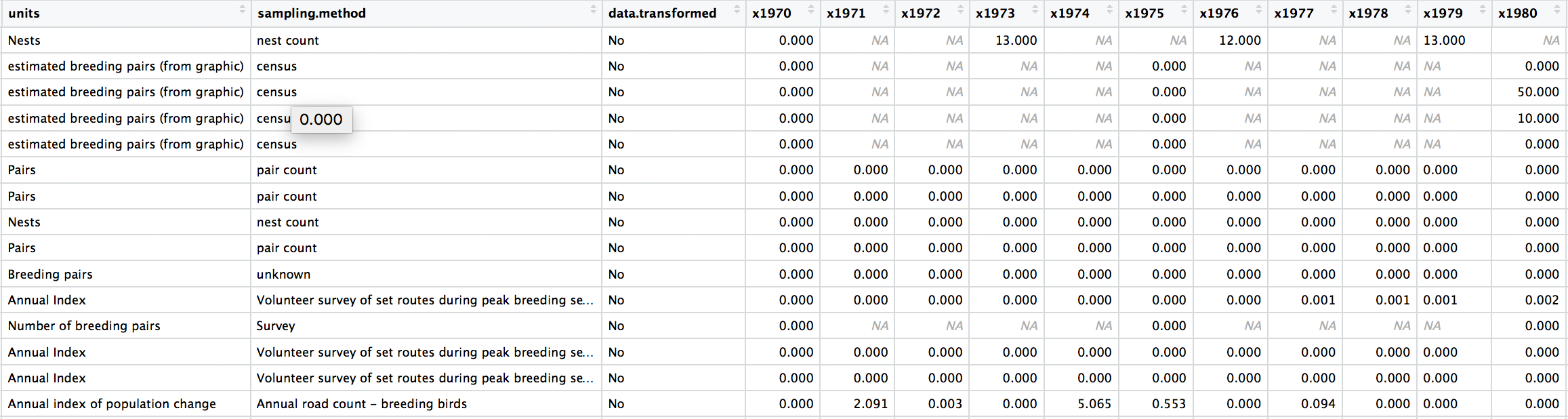

The data are in a wide format (each row contains a population that has been monitored over time and towards the right of the data frame there are lots of columns with population estimates for each year) and the column names are capitalised. Whenever working with data from different sources, chances are each dataset will follow a different column naming system, which can get confusing later on, so in general it is best to pick whatever naming system works for you and apply that to all datasets before you start working with them.

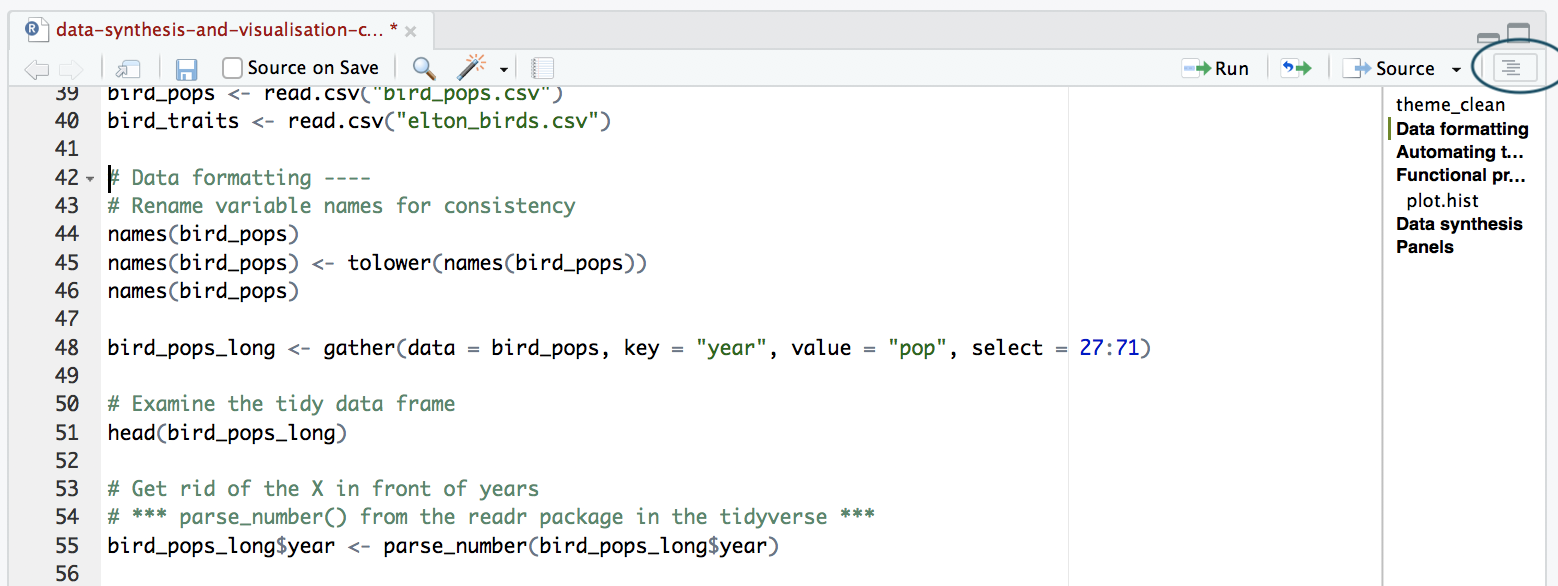

# Data formatting ----

# Rename variable names for consistency

names(bird_pops)

names(bird_pops) <- tolower(names(bird_pops))

names(bird_pops)

To make these data “tidy” (one column per variable and not the current wide format), we can use gather() to transform the data so there is a new column containing all the years for each population and an adjacent column containing all the population estimates for those years.

This takes our original dataset bird_pops and creates a new column called year, fills it with column names from columns 26:70 and then uses the data from these columns to make another column called pop.

bird_pops_long <- gather(data = bird_pops, key = "year", value = "pop", 27:71)

# Examine the tidy data frame

head(bird_pops_long)

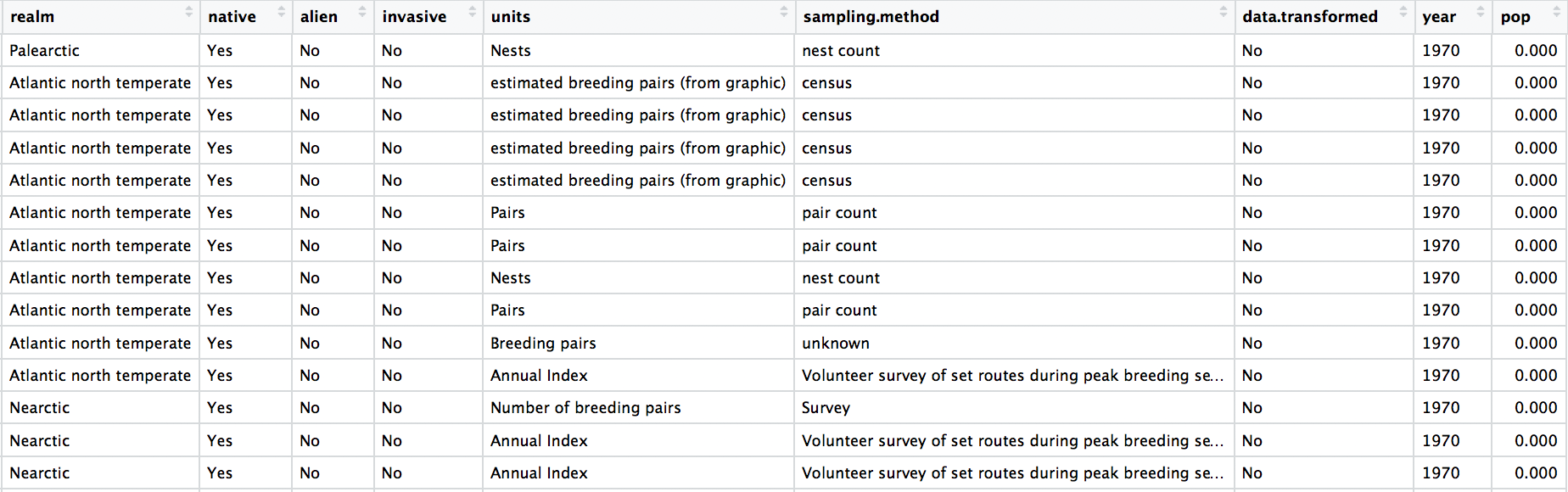

Because column names are coded in as characters, when we turned the column names (1970, 1971, 1972, etc.) into rows, R automatically put an X in front of the numbers to force them to remain characters. We don’t want that, so to turn year into a numeric variable, use the parse_number() function from the readr package.

# Get rid of the X in front of years

# *** parse_number() from the readr package in the tidyverse ***

bird_pops_long$year <- parse_number(bird_pops_long$year)

Check out the data frame again to make sure the years really look like years. As you’re looking through, you might notice something else. We have many columns in the data frame, but there isn’t a column with the species’ name. We can make one super quickly, since there are already columns for the genus and the species.

# Create new column with genus and species together

bird_pops_long$species.name <- paste(bird_pops_long$genus, bird_pops_long$species, sep = " ")

We can tidy up the data a bit more and create a few new columns with useful information. Whenever we are working with datasets that combine multiple studies, it’s useful to know when they each started, what their duration was, etc. Here we’ve combined all of that into one “pipe” (lines of code that use the piping operator %>%). The pipes always take whatever has come out of the previous pipe (or the first object you’ve given the pipe), and at the end of all the piping, out comes a tidy data frame with useful information.

# *** piping from from dplyr

bird_pops_long <- bird_pops_long %>%

# Remove duplicate rows

# *** distinct() function from dplyr

distinct() %>%

# remove NAs in the population column

# *** filter() function from dplyr

filter(is.finite(pop)) %>%

# Group rows so that each group is one population

# *** group_by() function from dplyr

group_by(id) %>%

# Make some calculations

# *** mutate() function from dplyr

mutate(maxyear = max(year), minyear = min(year),

# Calculate duration

duration = maxyear - minyear,

# Scale population trend data

scalepop = (pop - min(pop))/(max(pop) - min(pop))) %>%

# Keep populations with >5 years worth of data and calculate length of monitoring

filter(is.finite(scalepop),

length(unique(year)) > 5) %>%

# Remove any groupings you've greated in the pipe

ungroup()

head(bird_pops_long)

Now we can calculate some finer-scale summary statistics. Though we have the most ecological data we’ve ever had, there are still many remaining data gaps, and a lot of what we know about biodiversity is based on information coming from a small set of countries. Let’s check out which!

# Which countries have the most data

# Using "group_by()" to calculate a "tally"

# for the number of records per country

country_sum <- bird_pops %>% group_by(country.list) %>%

tally() %>%

arrange(desc(n))

country_sum[1:15,] # the top 15

As we probably all expected, a lot of the data come from Western European and North American countries. Sometimes as we navigate our research questions, we go back and forth between combining (adding in more data) and extracting (filtering to include only what we’re interested in), so to mimic that, this tutorial will similarly take you on a combining and extracting journey, this time through Australia.

To get just the Australian data, we can use the filter() function. To be on the safe side, we can also combine it with str_detect(). The difference is that filter on its own will extract any rows with “Australia”, but it will miss rows that have e.g. “Australia / New Zealand” - occasions when the population study included multiple countries. In this case though, both ways of filtering return the same number of rows, but always good to check.

# Data extraction ----

aus_pops <- bird_pops_long %>%

filter(country.list == "Australia")

# Giving the object a new name so that you can compare

# and see that in this case they are the same

aus_pops2 <- bird_pops_long %>%

filter(str_detect(country.list, pattern = "Australia"))

Managing long scripts: Lines of code pile up quickly! There is an outline feature in RStudio that makes long scripts more organised and easier to navigate. You can make a subsection by writing out a comment and adding four or more characters after the text, e.g. # Section 1 ----. If you’ve included all of the comments from the tutorial in your own script, you should already have some sections.

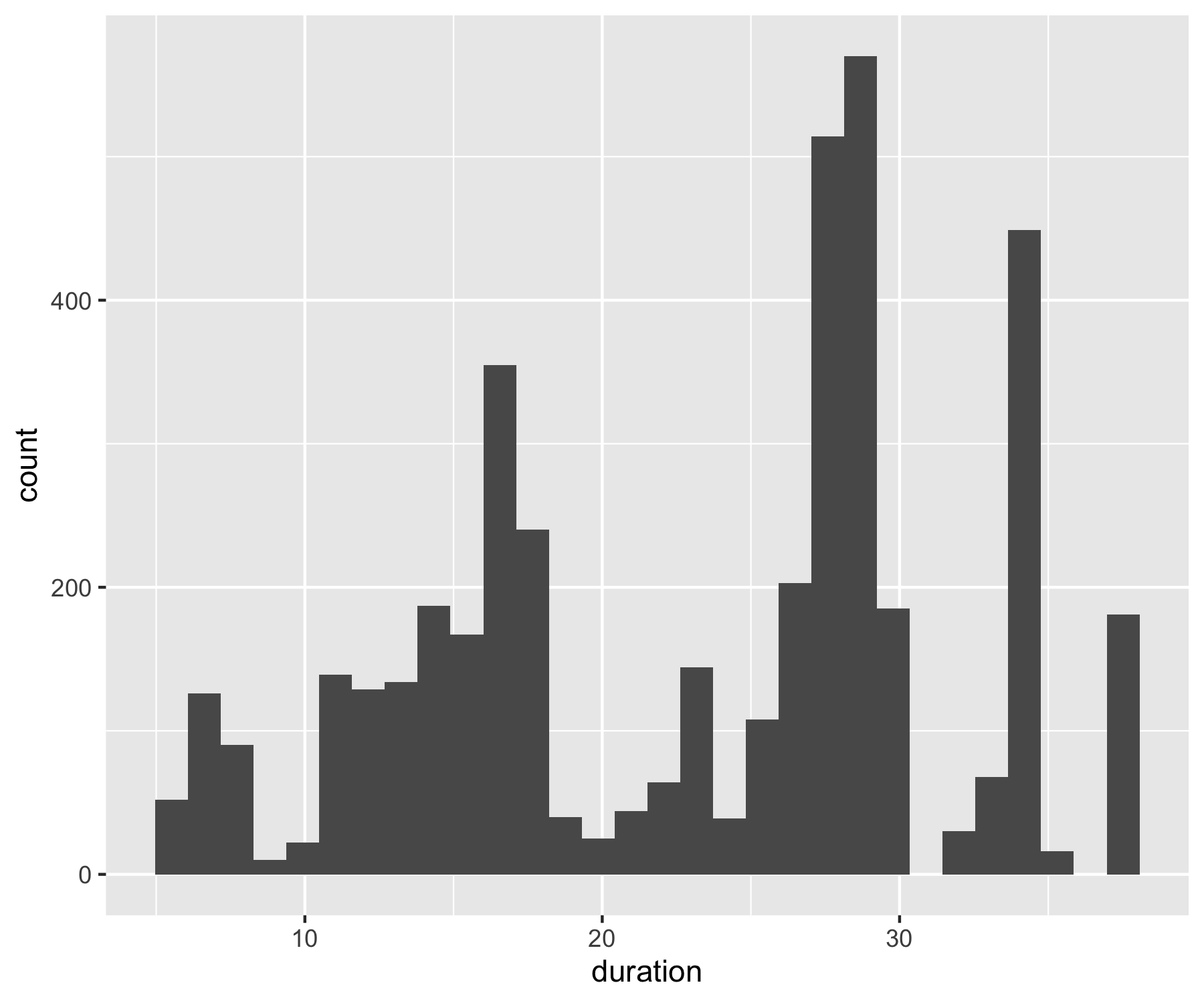

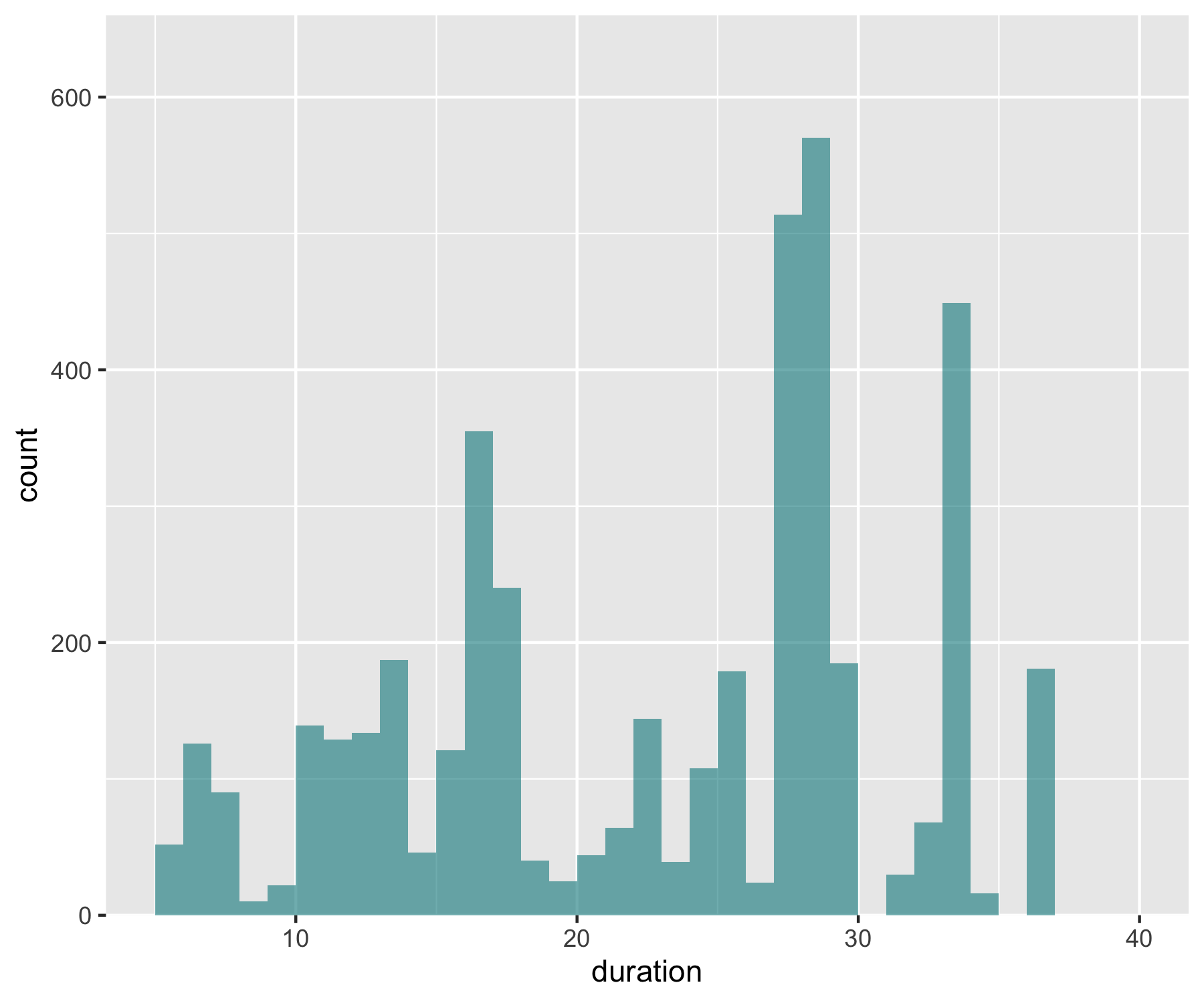

Now that we have our Australian bird population studies, we can learn more about the data by visualising the variation in study duration. Earlier on, we filtered to only include studies with more than five years of data, but it’s still useful to know how many studies have six years of data, and how many have much more.

An important note about graphs made using ggplot2: you’ll notice that throughout this tutorial, the ggplot2 code is always surrounded by brackets. That way, we both make the graph, assign it to an object, e.g. duration_hist and we “call” the graph, so we can see it in the plot tab. If you don’t have the brackets around the code chunk, you’ll make the graph, but you won’t actually see it. Alternatively, you can “call” the graph to the plot tab by running just the line duration_hist. It’s also best to assign your graphs to objects, especially if you want to save them later, otherwise they just disappear and you’ll have to run the code again to see or save the graph.

# Check the distribution of duration across the time-series

# A quick and not particularly pretty graph

(duration_hist <- ggplot(aus_pops, aes(x = duration)) +

geom_histogram())

This graph just uses all the ggplot2 default settings. It’s fine if you just want to see the distribution and move on, but if you plan to save the graph and share it with other people, we can make it way better. The figure beautification journey!

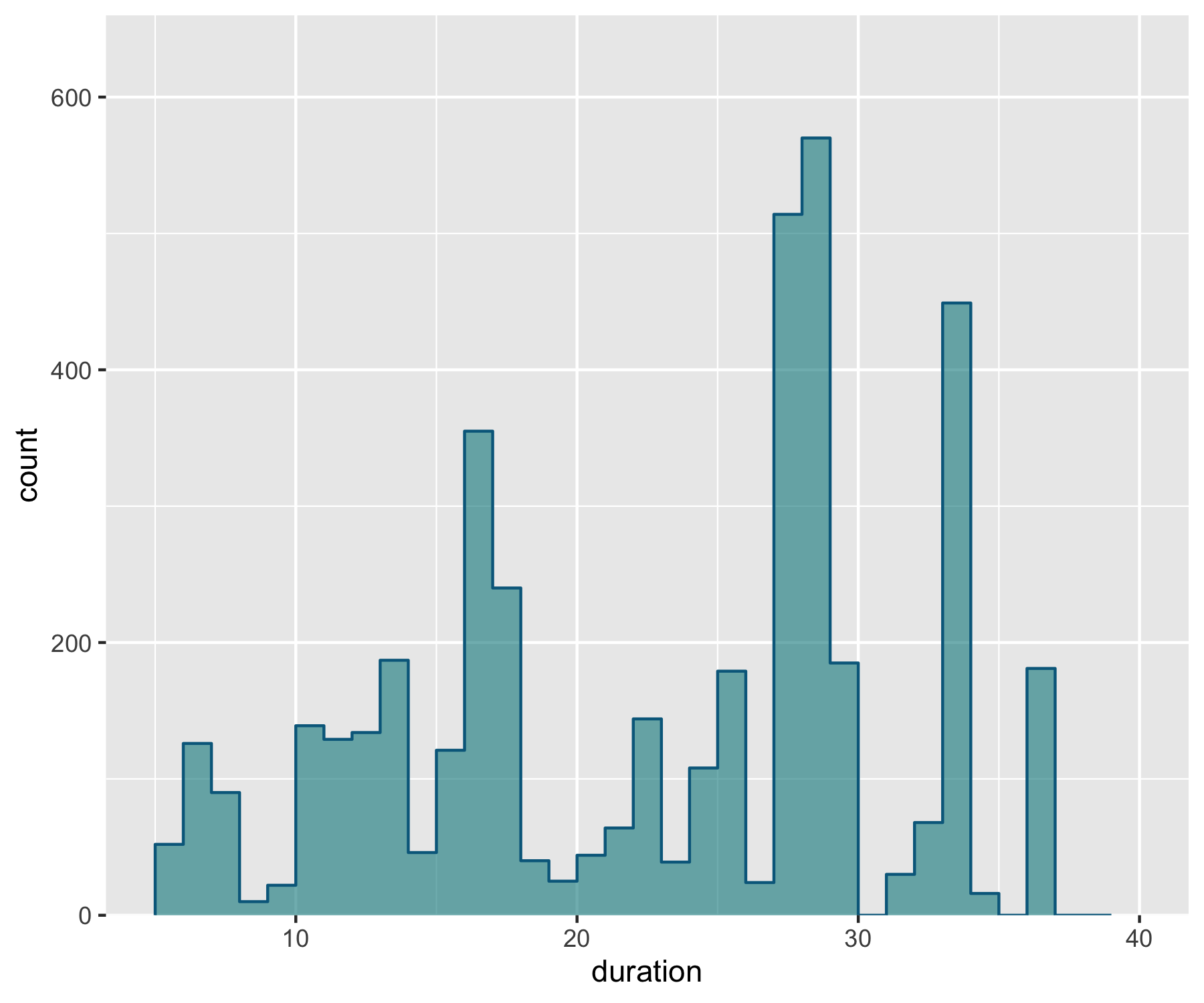

__ When using ggplot2, you usually start your code with ggplot(your_data, aes(x = independent_variable, y = dependent_variable)), then you add the type of plot you want to make using + geom_boxplot(), + geom_histogram(), etc. aes stands for aesthetics, hinting to the fact that using ggplot2 you can make aesthetically pleasing graphs - there are many ggplot2 functions to help you clearly communicate your results, and we will now go through some of them.__

When we want to change the colour, shape or fill of a variable based on another variable, e.g. colour-code by species, we include colour = species inside the aes() function. When we want to set a specific colour, shape or fill, e.g. colour = "black", we put that outside of the aes() function.

(duration_hist <- ggplot() +

geom_histogram(data = aus_pops, aes(x = duration), alpha = 0.6,

breaks = seq(5, 40, by = 1), fill = "turquoise4"))

(duration_hist <- ggplot(aus_pops, aes(x = duration)) +

geom_histogram(alpha = 0.6,

breaks = seq(5, 40, by = 1),

fill = "turquoise4") +

# setting new colours, changing the opacity and defining custom bins

scale_y_continuous(limits = c(0, 600), expand = expand_scale(mult = c(0, 0.1))))

# the final line of code removes the empty blank space below the bars

Now imagine you want to have a darker blue outline around the whole histogram - not around each individual bin, but the whole shape. It’s the little things that add up to make nice graphs! We can use geom_step() to create the histogram outline, but we have to put the steps in a data frame first. The three lines of code below are a bit of a cheat to create the histogram outline effect. Check out the object d1 to see what we’ve made.

# Adding an outline around the whole histogram

h <- hist(aus_pops$duration, breaks = seq(5, 40, by = 1), plot = FALSE)

d1 <- data.frame(x = h$breaks, y = c(h$counts, NA))

d1 <- rbind(c(5,0), d1)

When we want to plot data from different data frames in the same graph, we have to move the data frame from the main ggplot() call to the specific part of the graph where we want to use each dataset. Compare the code below with the code for the previous versions of the histograms to spot the difference.

(duration_hist <- ggplot() +

geom_histogram(data = aus_pops, aes(x = duration), alpha = 0.6,

breaks = seq(5, 40, by = 1), fill = "turquoise4") +

scale_y_continuous(limits = c(0, 600), expand = expand_scale(mult = c(0, 0.1))) +

geom_step(data = d1, aes(x = x, y = y),

stat = "identity", colour = "deepskyblue4"))

summary(d1) # it's fine, you can ignore the warning message

# it's because some values don't have bars

# thus there are missing "steps" along the geom_step path

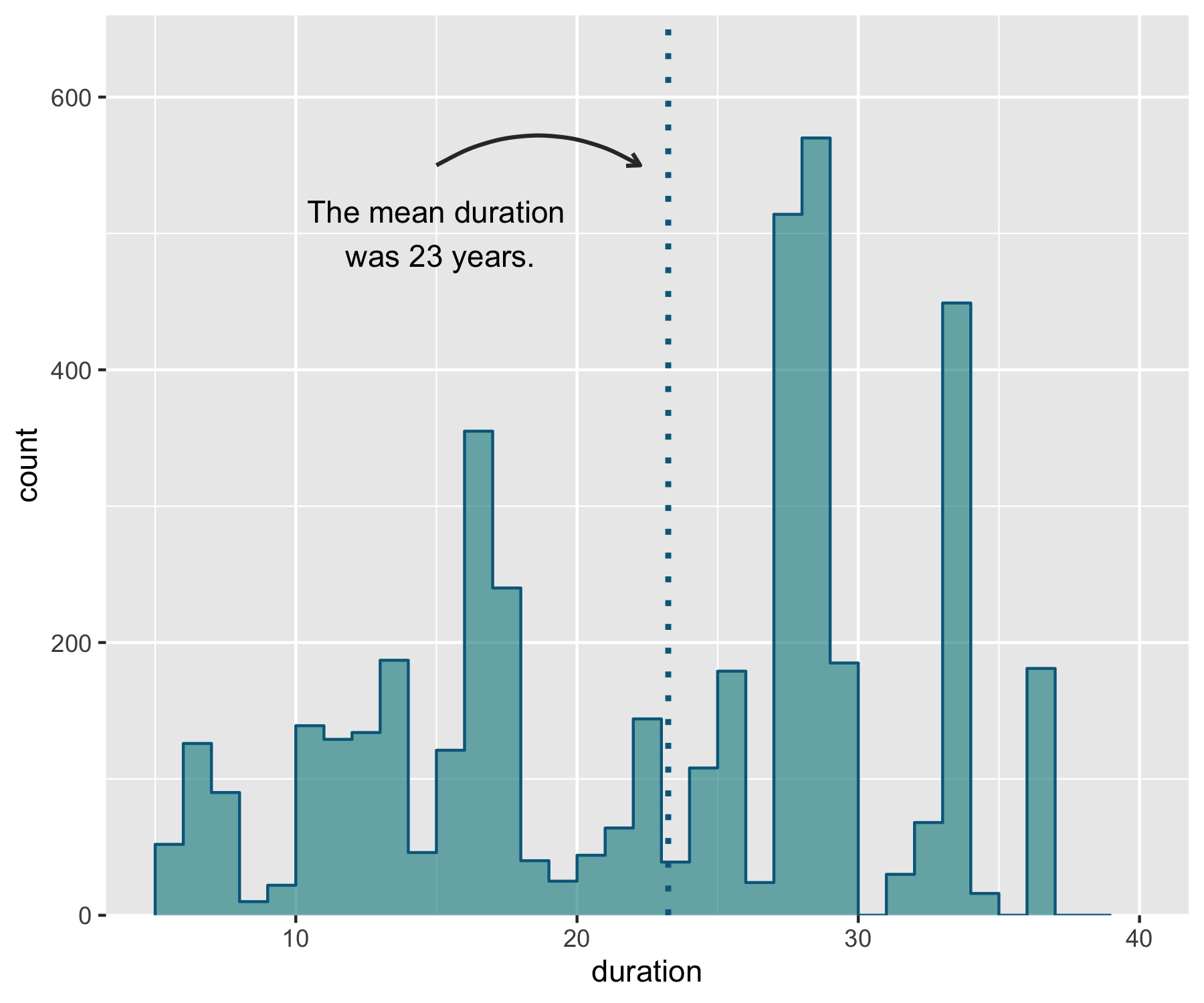

We can also add a line for the mean duration across studies and add an annotation on the graph so that people can quickly see what the line means.

(duration_hist <- ggplot() +

geom_histogram(data = aus_pops, aes(x = duration), alpha = 0.6,

breaks = seq(5, 40, by = 1), fill = "turquoise4") +

scale_y_continuous(limits = c(0, 600), expand = expand_scale(mult = c(0, 0.1))) +

geom_step(data = d1, aes(x = x, y = y),

stat = "identity", colour = "deepskyblue4") +

geom_vline(xintercept = mean(aus_pops$duration), linetype = "dotted",

colour = "deepskyblue4", size = 1))

(duration_hist <- ggplot() +

geom_histogram(data = aus_pops, aes(x = duration), alpha = 0.6,

breaks = seq(5, 40, by = 1), fill = "turquoise4") +

scale_y_continuous(limits = c(0, 600), expand = expand_scale(mult = c(0, 0.1))) +

geom_step(data = d1, aes(x = x, y = y),

stat = "identity", colour = "deepskyblue4") +

geom_vline(xintercept = mean(aus_pops$duration), linetype = "dotted",

colour = "deepskyblue4", size = 1) +

# Adding in a text allocation - the coordinates are based on the x and y axes

annotate("text", x = 15, y = 500, label = "The mean duration\n was 23 years.") +

# "\n" creates a line break

geom_curve(aes(x = 15, y = 550, xend = mean(aus_pops$duration) - 1, yend = 550),

arrow = arrow(length = unit(0.07, "inch")), size = 0.7,

color = "grey20", curvature = -0.3))

# Similarly to the annotation, the curved line follows the plot's coordinates

# Have a go at changing the curve parameters to see what happens

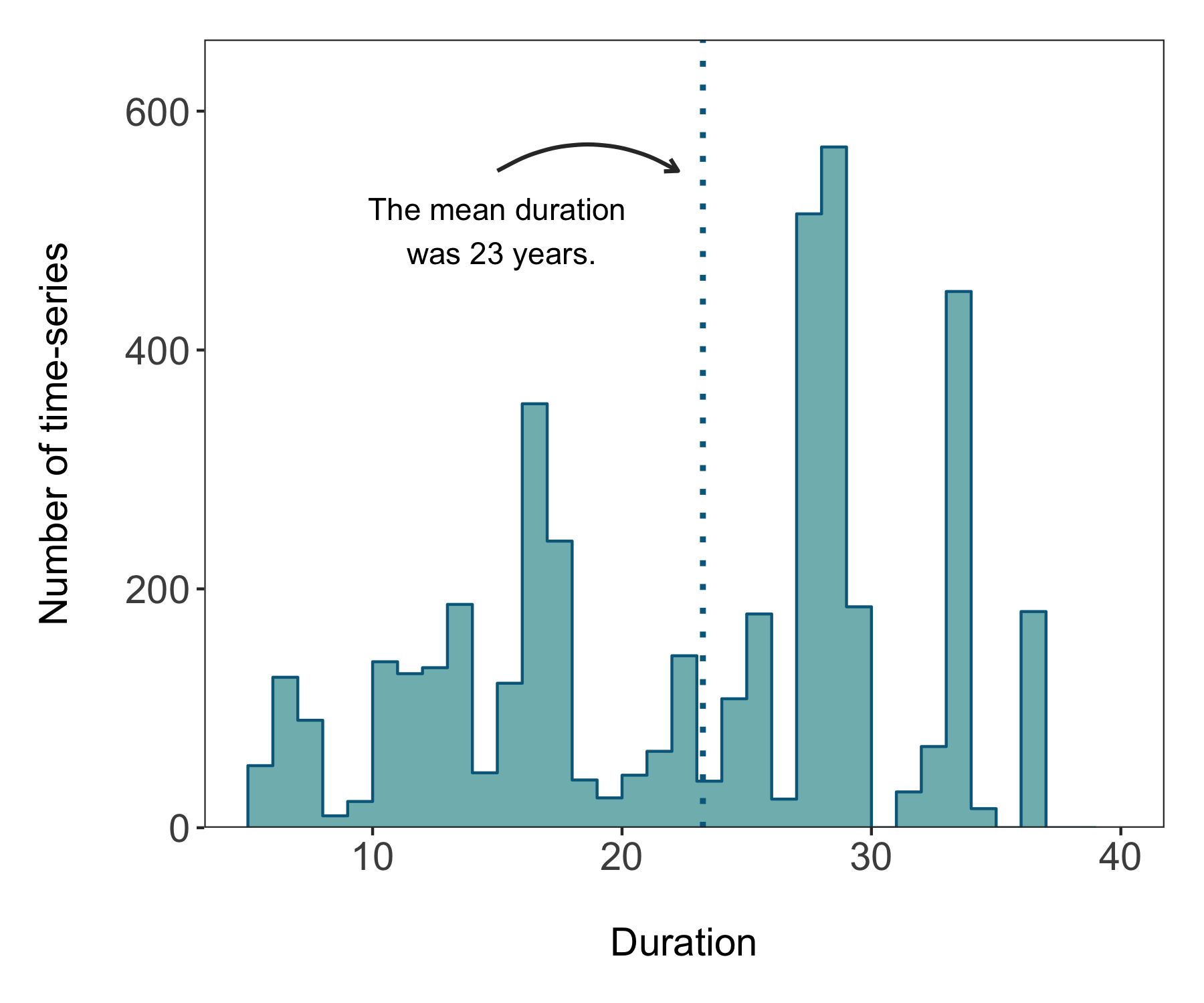

We are super close to a nice histogram - all we are missing is letting it “shine”. The default ggplot2 theme is a bit cluttered and the grey background and lines distract from the main message of the graph. At the start of the tutorial we made our own clean theme, time to put it in action!

(duration_hist <- ggplot() +

geom_histogram(data = aus_pops, aes(x = duration), alpha = 0.6,

breaks = seq(5, 40, by = 1), fill = "turquoise4") +

scale_y_continuous(limits = c(0, 600), expand = expand_scale(mult = c(0, 0.1))) +

geom_step(data = d1, aes(x = x, y = y),

stat = "identity", colour = "deepskyblue4") +

geom_vline(xintercept = mean(aus_pops$duration), linetype = "dotted",

colour = "deepskyblue4", size = 1) +

annotate("text", x = 15, y = 500, label = "The mean duration\n was 23 years.") +

geom_curve(aes(x = 15, y = 550, xend = mean(aus_pops$duration) - 1, yend = 550),

arrow = arrow(length = unit(0.07, "inch")), size = 0.7,

color = "grey20", curvature = -0.3) +

labs(x = "\nDuration", y = "Number of time-series\n") +

theme_clean())

There’s our histogram! We can save it using ggsave. The units for the height and width are in inches. Unless you specify a different file path, the graph will go in your working directory. If you’ve forgotten where that is, you can easily find out by running getwd() in the console.

ggsave(duration_hist, filename = "hist1.png",

height = 5, width = 6)

2. Automate repetitive tasks using pipes and functions

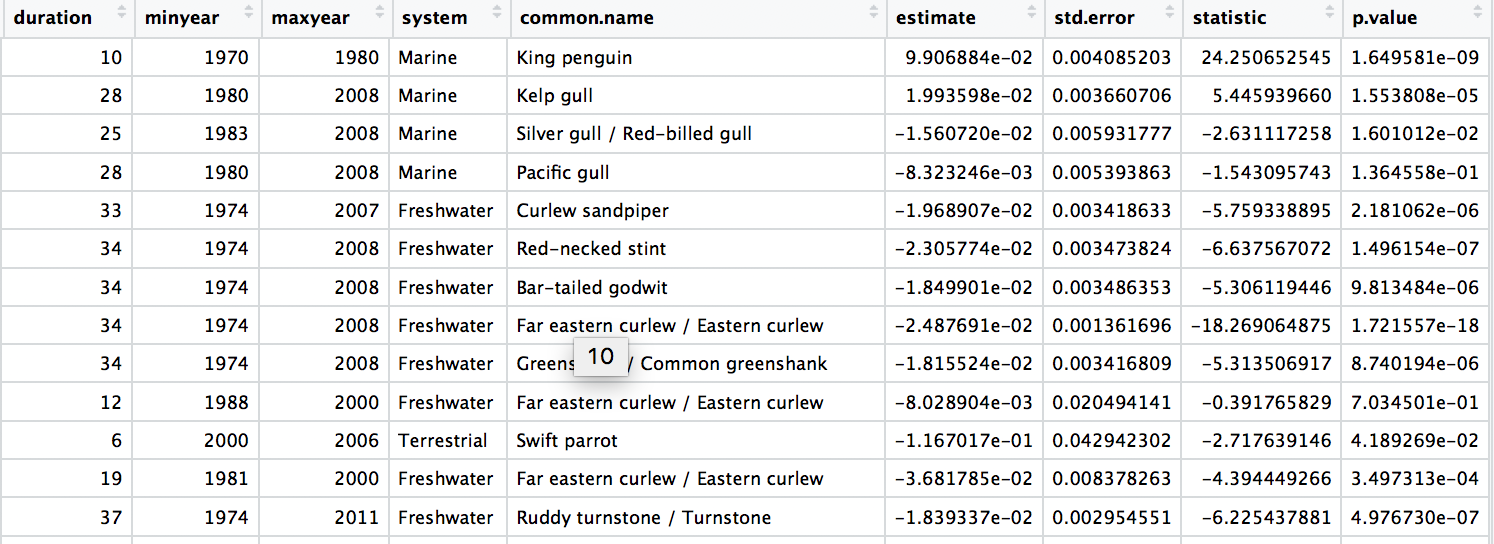

We are now ready to model how each population has changed over time. There are 4331 populations, so with this one code chunk, we will run 4331 models and tidy up their outputs. You can read through the line-by-line comments to get a feel for what each line of code is doing.

One specific thing to note is that when you add the lm() function in a pipe, you have to add data = ., which means use the outcome of the previous step in the pipe for the model.

A piping tip: A useful way to familiriase yourself with what the pipe does at each step is to ‘break’ the pipe and check out what the resulting object looks like if you’ve only ran the code up to e.g., the do() function, then up to the tidy() function and so on. You can do that by just select the relevant bit of code and running only that, but remember you have to exclude the piping operator at the end of the line, so e.g. you select up to do(mod = lm(scalepop ~ year, data = .)) and not the whole do(mod = lm(scalepop ~ year, data = .)) %>%.

Running pipes sequentially line by line also comes in handy when there is an error in your pipe and you don’t know which part exactly introduces the error.

# Calculate population change for each forest population

# 4331 models in one go!

# Using a pipe

aus_models <- aus_pops %>%

# Group by the key variables that we want to iterate over

# note that if we only include e.g. id (the population id), then we only get the

# id column in the model summary, not e.g. duration, latitude, class...

group_by(decimal.latitude, decimal.longitude, class,

species.name, id, duration, minyear, maxyear,

system, common.name) %>%

# Create a linear model for each group

do(mod = lm(scalepop ~ year, data = .)) %>%

# Extract model coefficients using tidy() from the

# *** tidy() function from the broom package ***

tidy(mod) %>%

# Filter out slopes and remove intercept values

filter(term == "year") %>%

# Get rid of the column term as we don't need it any more

# *** select() function from dplyr in the tidyverse ***

dplyr::select(-term) %>%

# Remove any groupings you've greated in the pipe

ungroup()

head(aus_models)

# Check out the model data frame

Next up, we will focus on automating iterative actions, for example when we want to create the same type of graph for different subsets of our data. In our case, we will make histograms of the population change experienced by birds across three different systems - marine, freshwater and terrestrial. When making multiple graphs at once, we have to specify the folder where they will be saved first.

# Make histograms of slope estimates for each system -----

# Set up new folder for figures

# Set path to relevant path on your computer/in your repository

path1 <- "system_histograms/"

# Create new folder

dir.create(path1) # skip this if you want to use an existing folder

# but remember to replace the path in "path1" if you're changing the folder

# First we will do this using dplyr and a pipe

aus_models %>%

# Select the relevant data

dplyr::select(id, system, species.name, estimate) %>%

# Group by taxa

group_by(system) %>%

# Save all plots in new folder

do(ggsave(ggplot(., aes(x = estimate)) +

# Add histograms

geom_histogram(colour = "deepskyblue4", fill = "turquoise4", binwidth = 0.02) +

# Use custom theme

theme_clean() +

# Add axis lables

xlab("Population trend (slopes)"),

# Set up file names to print to

filename = gsub("", "", paste0(path1, unique(as.character(.$system)),

".pdf")), device = "pdf"))

A warning message pops up: Error: Results 1, 2, 3, 4 must be data frames, not NULL - you can ignore this, it’s because the do() function expects a data frame as an output, but in our case we are making graphs, not data frames.

Check out your folder, you should see three graphs in there! You can use pipes to make way more than just three graphs at once, it just so happens that our grouping variable has only three levels, but if it had thirty levels, there would be thirty graphs in the folder.

Another way to make all those histograms in one go is by creating a function for it. In general, whenever you find yourself copying and pasting lots of code only to change the object name, you’re probably in a position to swap all the code with a function - you can then apply the function using the purrr package.

But what is purrr? It is a way to “map” or “apply” functions to data. Note that there are functions from other packages also called map(), which is why we are specifying we want the map() function from the purrr package. Here we will first format the data aus_models_wide and then we will map it to the mean fuction:

We have to change the format of the data, in our case we will split the data using spread() from the tidyr package.

# Selecting the relevant data and splitting it into a list

aus_models_wide <- aus_models %>%

dplyr::select(id, system, estimate) %>%

spread(system, estimate) %>%

dplyr::select(-id)

# We can apply the `mean` function using `purrr::map()`:

system.mean <- purrr::map(aus_models_wide, ~mean(., na.rm = TRUE))

# Note that we have to specify "."

# so that the function knows to use our taxa.slopes object

# This plots the mean population change per taxa

system.mean

Now we can write our own function to make histograms and use the purrr package to apply it to each taxa.

### Using functions ----

# First let's write a function to make the plots

# This function takes one argument x, the data vector that we want to make a histogram

# note that when you run code for a function, you have to place the cursor

# on the first line (so not in the middle of the function) and then run it

# otherwise you get an error

# For most other things (like normal ggplot2 code, it doesn't matter

# if the cursor is on the first line, or the 3rd, 5th...)

plot.hist <- function(x) {

ggplot() +

geom_histogram(aes(x), colour = "deepskyblue4", fill = "turquoise4", binwidth = 0.02) +

theme_clean() +

xlab("Population trend (slopes)")

}

Now we can use purr to “map” our figure making function. The first input is your data that you want to iterate over and the second input is the function.

system.plots <- purrr::map(aus_models_wide, ~plot.hist(.))

# We need to make a new folder to put these figures in

path2 <- "system_histograms_purrr/"

dir.create(path2)

We’ve learned about map(), but there are other purrr functions,too, and we still need to actually save our graphs.

walk2() takes two arguments and returns nothing. In our case we just want to print the graphs, so we don’t need anything returned. The first argument is our file path, the second is our data and ggsave is our function.

# *** walk2() function in purrr from the tidyverse ***

walk2(paste0(path2, names(aus_models_wide), ".pdf"), system.plots, ggsave)

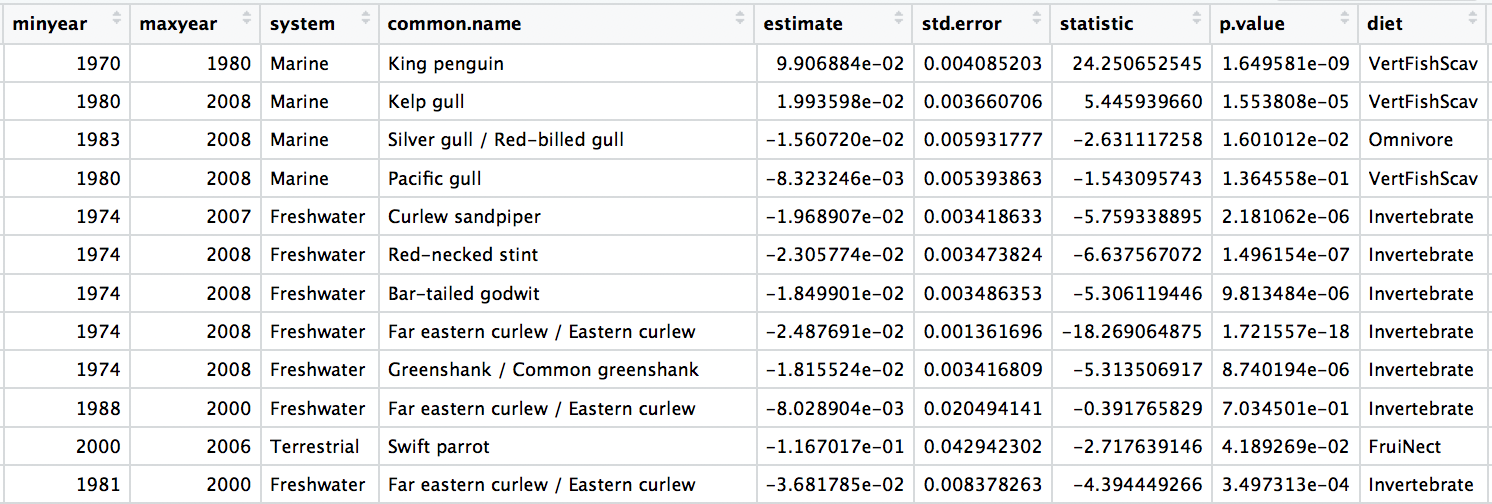

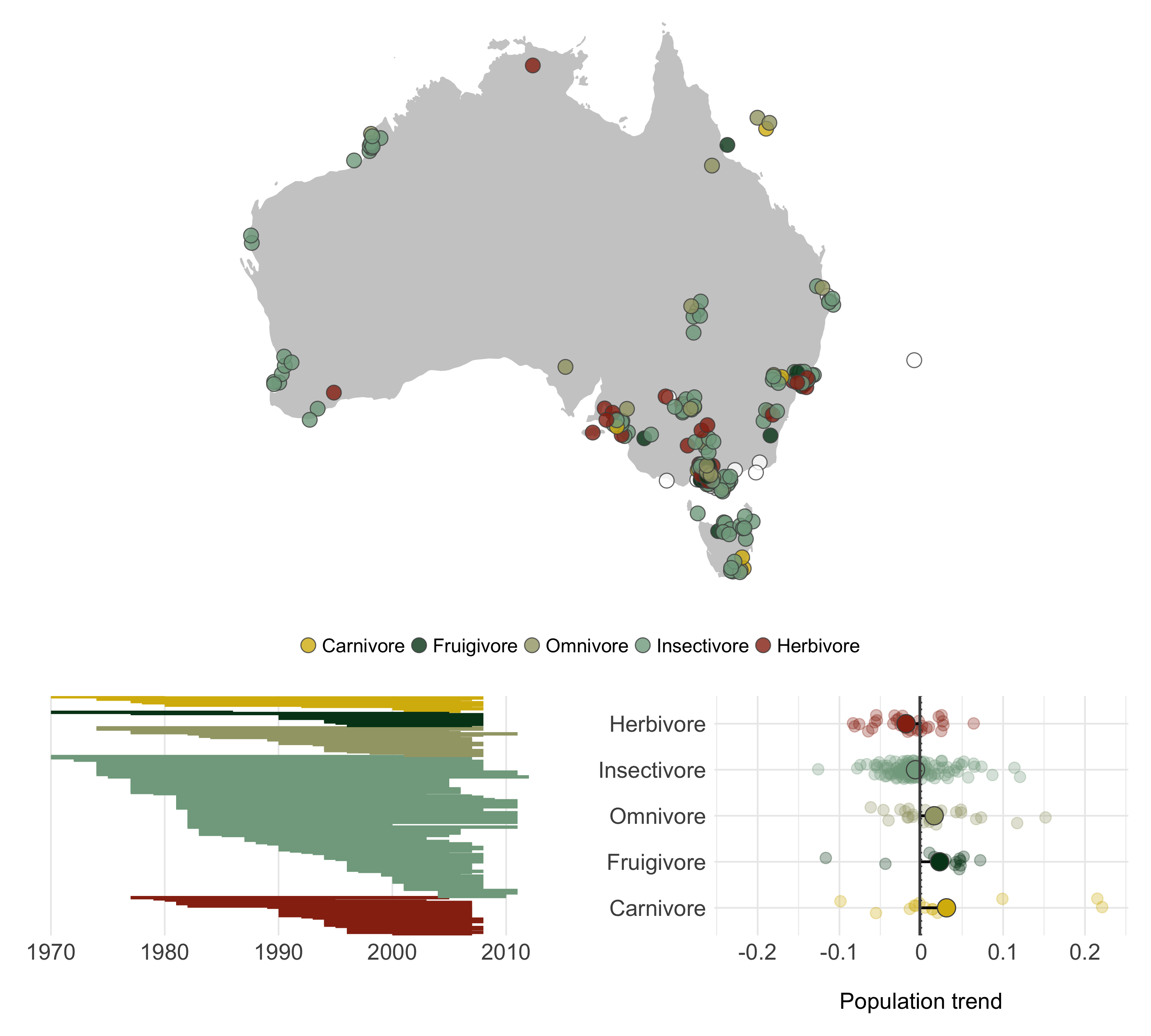

3. Synthesise information from different databases

Answering research questions often requires combining data from different sources. For example, we’ve explored how bird abundance has changed over time across the monitored populations in Australia, but we don’t know whether certain groups of species might be more likely to increase or decrease. To find out, we can integrate the population trend data with information on species traits, in this case species’ diet preferences.

The various joining functions from the dplyr package are really useful for combining data. We will use left_join in this tutorial, but you can find out about all the other options by running ?join() and reading the help file. To join two datasets in a meaningful way, you usually need to have one common column in both data frames and then you join “by” that column.

# Data synthesis - traits! ----

# Tidying up the trait data

# similar to how we did it for the population data

colnames(bird_traits)

bird_traits <- bird_traits %>% rename(species.name = Scientific)

# rename is a useful way to change column names

# it goes new name = old name

colnames(bird_traits)

# Select just the species and their diet

bird_diet <- bird_traits %>% dplyr::select(species.name, `Diet.5Cat`) %>%

distinct() %>% rename(diet = `Diet.5Cat`)

# Combine the two datasets

# The second data frame will be added to the first one

# based on the species column

bird_models_traits <- left_join(aus_models, bird_diet, by = "species.name") %>%

drop_na()

head(bird_models_traits)

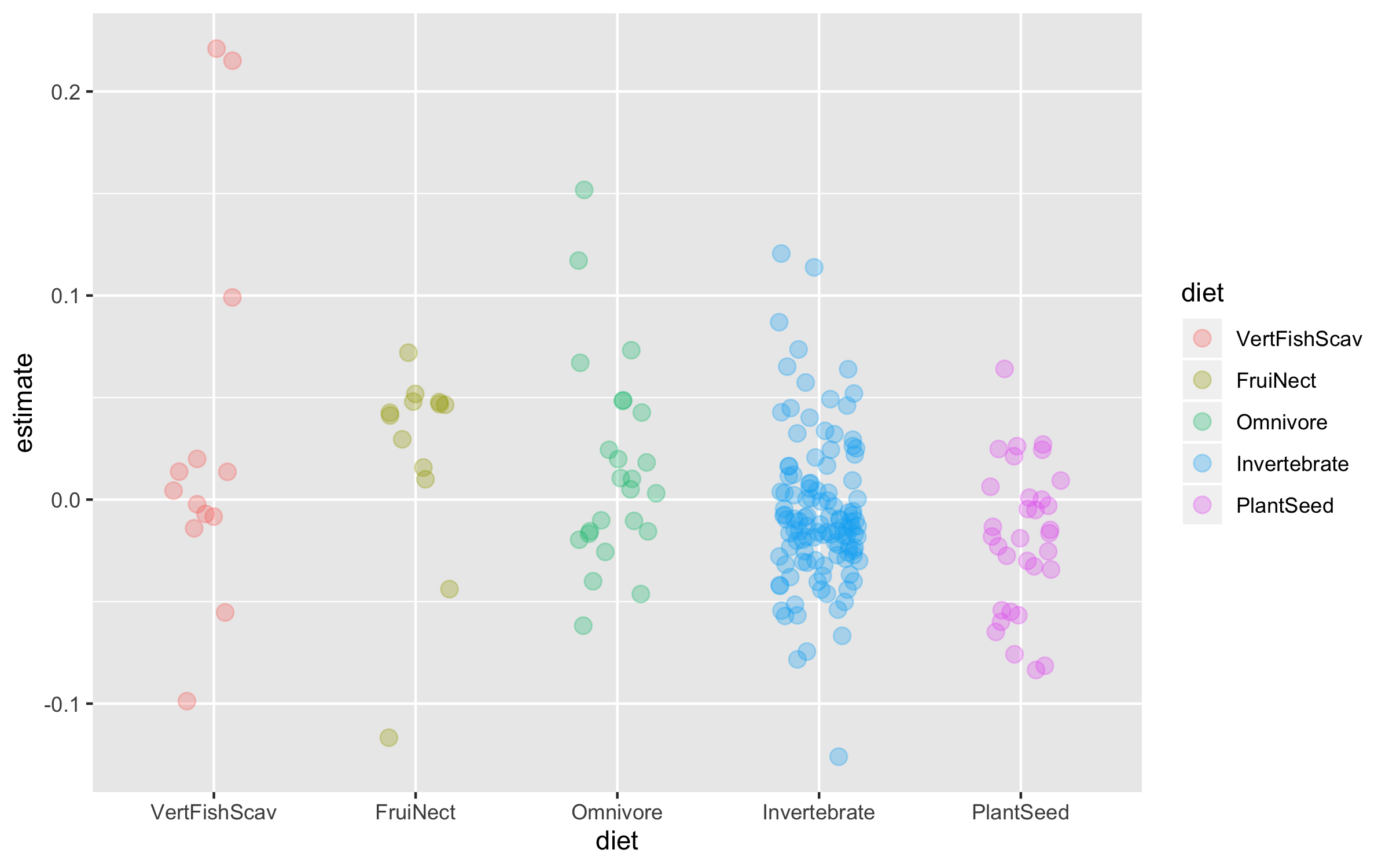

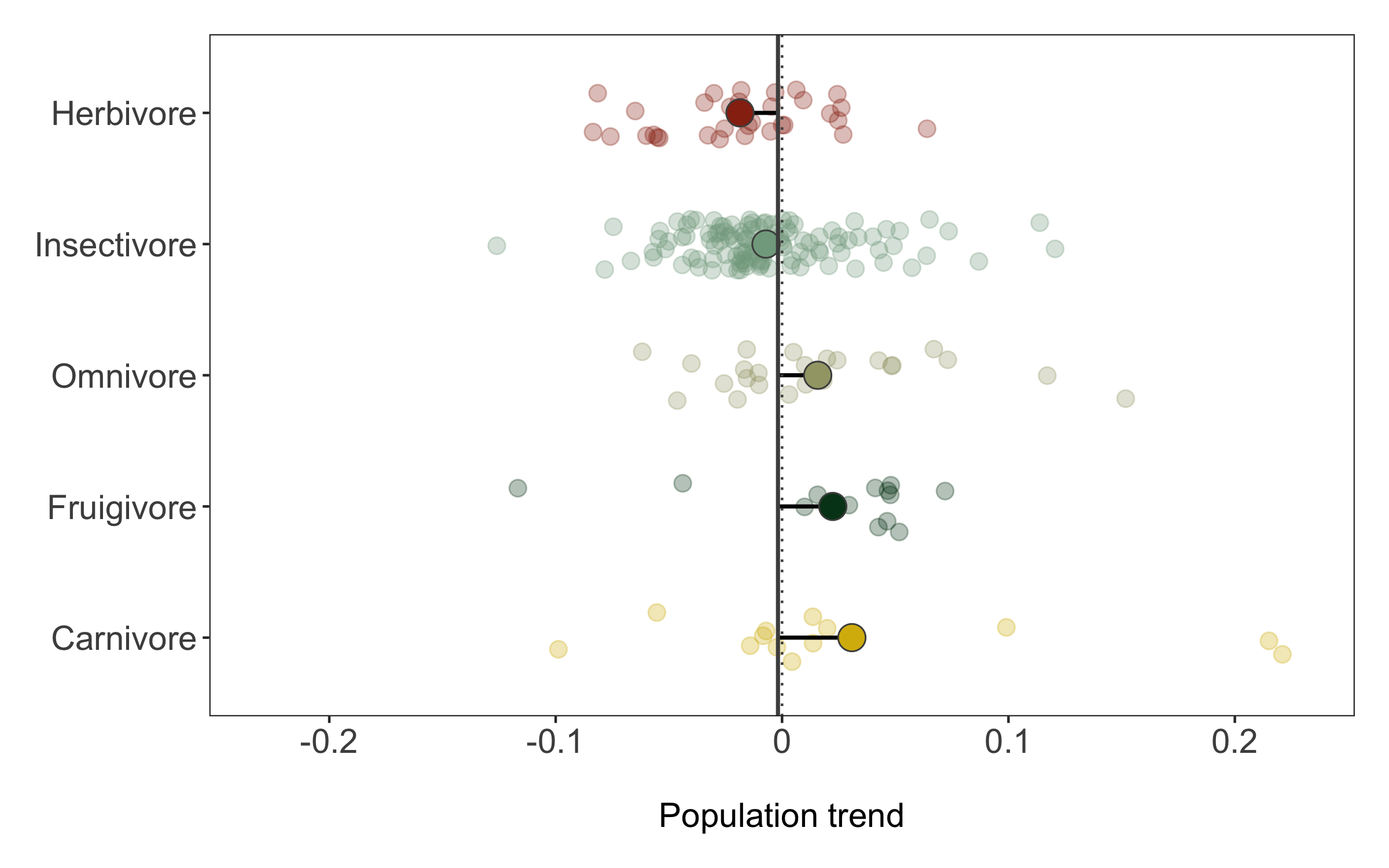

Now we can explore how bird population trends vary across different feeding strategies. The graphs below are all different ways to answer the same question. Have a ponder about which graph you like the most.

(trends_diet <- ggplot(bird_models_traits, aes(x = diet, y = estimate,

colour = diet)) +

geom_boxplot())

(trends_diet <- ggplot(data = bird_models_traits, aes(x = diet, y = estimate,

colour = diet)) +

geom_jitter(size = 3, alpha = 0.3, width = 0.2))

To make the graph more informative, we can add a line for the overall mean population trend, and then we can easily compare how the diet-specific trends compare to the overall mean trend. We can also plot the mean trend per diet category and we can sort the graph so that it goes from declines to increases.

# Calculating mean trends per diet categories

diet_means <- bird_models_traits %>% group_by(diet) %>%

summarise(mean_trend = mean(estimate)) %>%

arrange(mean_trend)

# Sorting the whole data frame by the mean trends

bird_models_traits <- bird_models_traits %>%

group_by(diet) %>%

mutate(mean_trend = mean(estimate)) %>%

ungroup() %>%

mutate(diet = fct_reorder(diet, -mean_trend))

Finally, we can also use geom_segment to connect the points for the mean trends to the line for the overall mean, so we can judge how far off each category is from the mean.

(trends_diet <- ggplot() +

geom_jitter(data = bird_models_traits, aes(x = diet, y = estimate,

colour = diet),

size = 3, alpha = 0.3, width = 0.2) +

geom_segment(data = diet_means,aes(x = diet, xend = diet,

y = mean(bird_models_traits$estimate),

yend = mean_trend),

size = 0.8) +

geom_point(data = diet_means, aes(x = diet, y = mean_trend,

fill = diet), size = 5,

colour = "grey30", shape = 21) +

geom_hline(yintercept = mean(bird_models_traits$estimate),

size = 0.8, colour = "grey30") +

geom_hline(yintercept = 0, linetype = "dotted", colour = "grey30") +

coord_flip() +

theme_clean() +

scale_colour_manual(values = wes_palette("Cavalcanti1")) +

scale_fill_manual(values = wes_palette("Cavalcanti1")) +

scale_y_continuous(limits = c(-0.23, 0.23),

breaks = c(-0.2, -0.1, 0, 0.1, 0.2),

labels = c("-0.2", "-0.1", "0", "0.1", "0.2")) +

scale_x_discrete(labels = c("Carnivore", "Fruigivore", "Omnivore", "Insectivore", "Herbivore")) +

labs(x = NULL, y = "\nPopulation trend") +

guides(colour = FALSE, fill = FALSE))

Like before, we can save the graph using ggsave.

ggsave(trends_diet, filename = "trends_diet.png",

height = 5, width = 8)

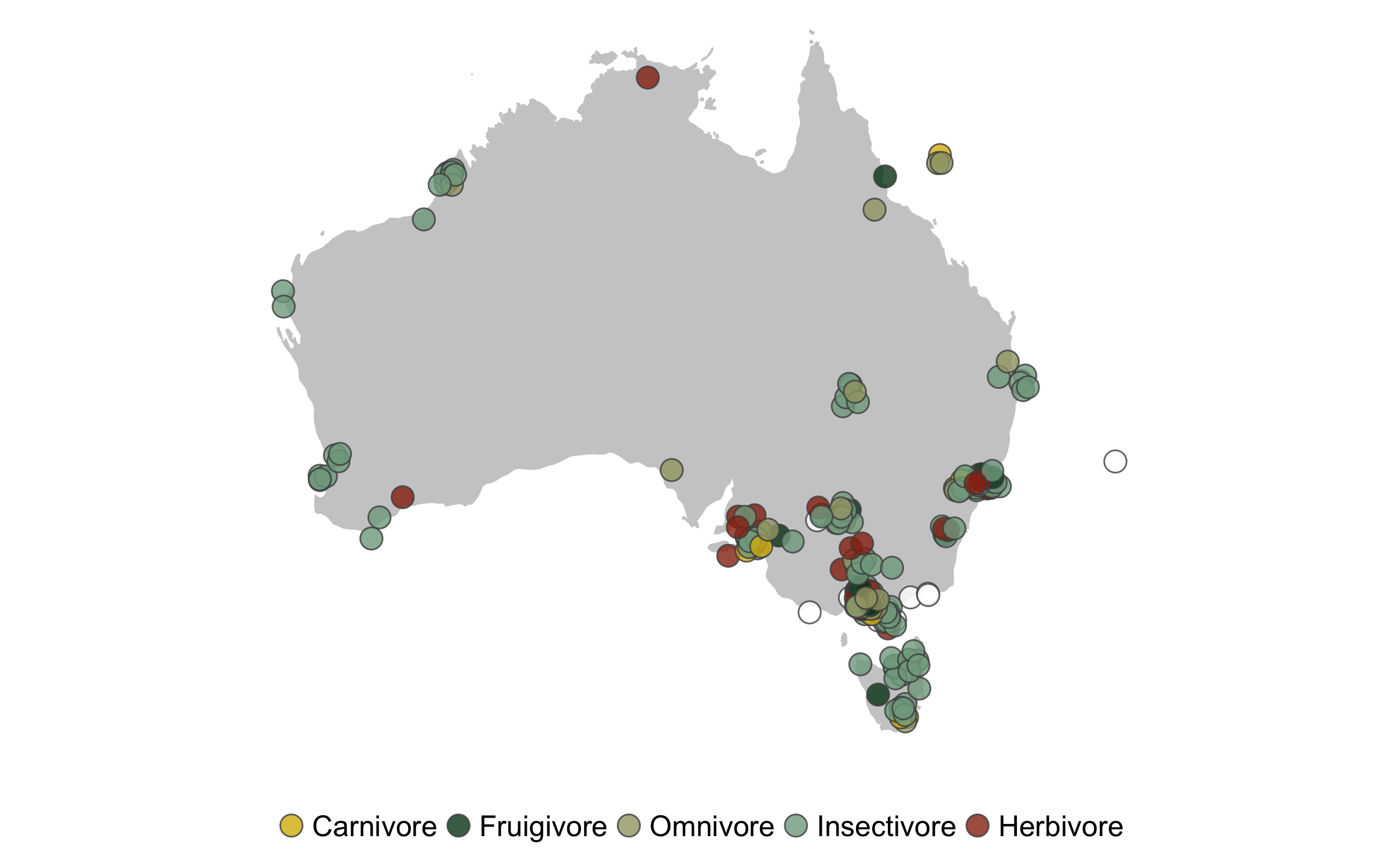

When working with lots of data, another common type of data visualisation is a map so that we can see where all the different studies come from.

# Get the shape of Australia

australia <- map_data("world", region = "Australia")

# Make an object for the populations which don't have trait data

# so that we can plot them too

# notice the use of anti_join that only returns rows

# in the first data frame that don't have matching rows

# in the second data frame

bird_models_no_traits <- anti_join(aus_models, bird_diet, by = "species.name")

For our map, we’ll use a colour scheme from the wesanderson R package and we’ll also jitter the points a bit so that there is less overlap. We’ll also rename the diet categories just for the legend. We’ll use the Mercator projection, which is not the best for global maps, but works fine for just Australia. The coord_proj function is very useful (it’s from the ggalt package as it allows us to use a wide variety of projections. You can find the full list here, once you’ve found the one you want, you just need to copy the projection string for it and replace +proj=merc with the one you want.

(map <- ggplot() +

geom_map(map = australia, data = australia,

aes(long, lat, map_id = region),

color = "gray80", fill = "gray80", size = 0.3) +

# you can change the projection here

coord_proj(paste0("+proj=merc"), ylim = c(-9, -45)) +

theme_map() +

geom_point(data = bird_models_no_traits,

aes(x = decimal.longitude, y = decimal.latitude),

alpha = 0.8, size = 4, fill = "white", colour = "grey30",

shape = 21,

position = position_jitter(height = 0.5, width = 0.5)) +

geom_point(data = bird_models_traits,

aes(x = decimal.longitude, y = decimal.latitude, fill = diet),

alpha = 0.8, size = 4, colour = "grey30", shape = 21,

position = position_jitter(height = 0.5, width = 0.5)) +

scale_fill_manual(values = wes_palette("Cavalcanti1"),

labels = c("Carnivore", "Fruigivore", "Omnivore", "Insectivore", "Herbivore")) +

# guides(colour = FALSE) + # if you wanted to hide the legend

theme(legend.position = "bottom",

legend.title = element_blank(),

legend.text = element_text(size = 12),

legend.justification = "top"))

# You don't need to worry about the warning messages

# that's just cause we've overwritten the default projection

ggsave(map, filename = "map1.png",

height = 5, width = 8)

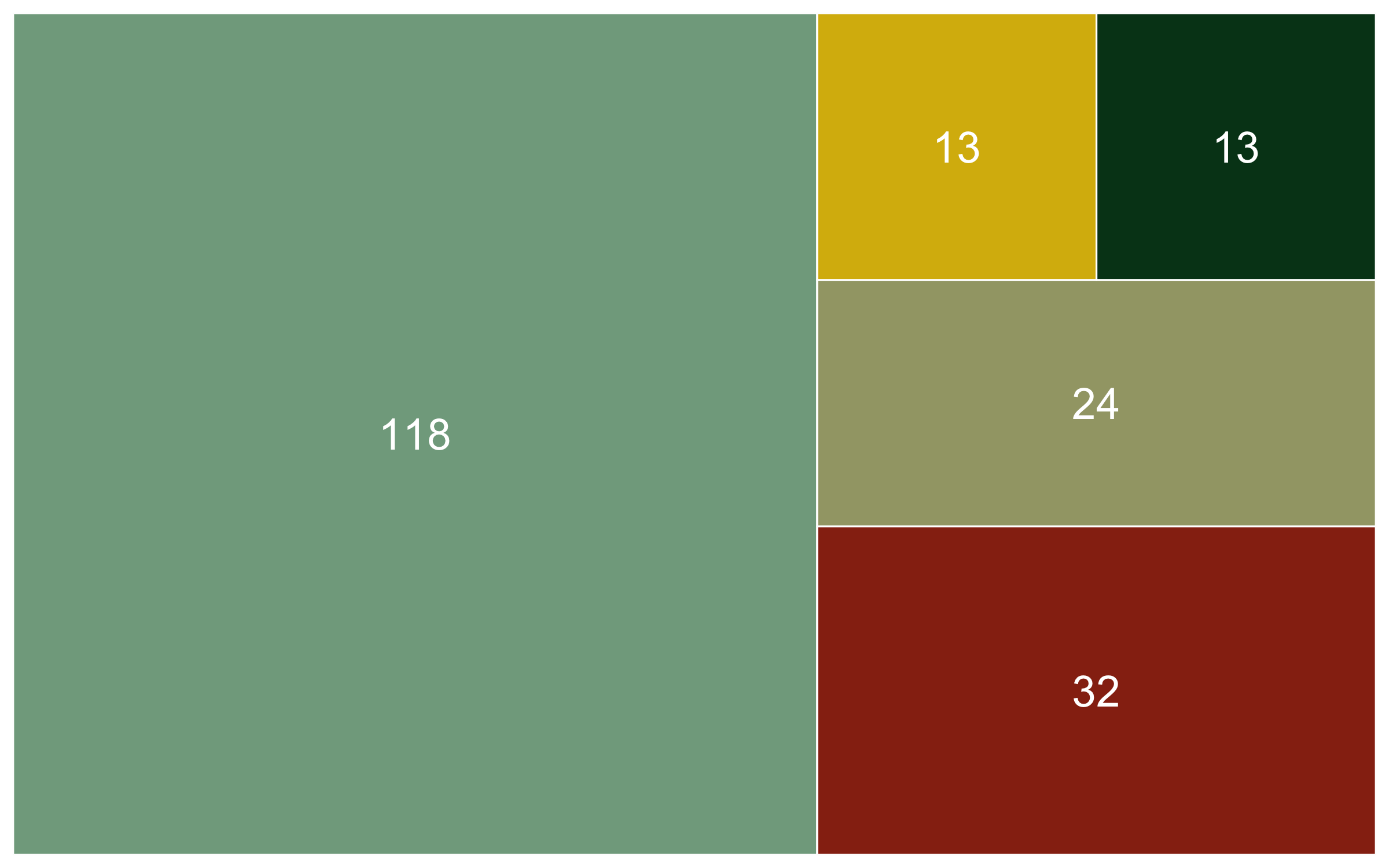

Knowing the sample size for each diet category is another useful bit of information, especially to support the spirit of open and transparent science. We can use group_by() and tally() to get the sample size numbers.

diet_sum <- bird_models_traits %>% group_by(diet) %>%

tally()

Now that we know the numbers, we can visualise them. A barplot would be a classic way to do that, the second option present here - the area graph - is another option. Both can work well depending on the specific occasion, but the area graph does a good job at quickly communicating which categories are overrepresented and which - underrepresented.

(diet_bar <- ggplot(diet_sum, aes(x = diet, y = n,

colour = diet,

fill = diet)) +

geom_bar(stat = "identity") +

scale_colour_manual(values = wes_palette("Cavalcanti1")) +

scale_fill_manual(values = wes_palette("Cavalcanti1")) +

guides(fill = FALSE))

(diet_area <- ggplot(diet_sum, aes(area = n, fill = diet, label = n,

subgroup = diet)) +

geom_treemap() +

geom_treemap_subgroup_border(colour = "white", size = 1) +

geom_treemap_text(colour = "white", place = "center", reflow = T) +

scale_colour_manual(values = wes_palette("Cavalcanti1")) +

scale_fill_manual(values = wes_palette("Cavalcanti1")) +

guides(fill = FALSE)) # this removes the colour legend

# later on we will combine multiple plots so there is no need for the legend

# to be in twice

# To display the legend, just remove the guides() line

(diet_area <- ggplot(diet_sum, aes(area = n, fill = diet, label = n,

subgroup = diet)) +

geom_treemap() +

geom_treemap_subgroup_border(colour = "white", size = 1) +

geom_treemap_text(colour = "white", place = "center", reflow = T) +

scale_colour_manual(values = wes_palette("Cavalcanti1")) +

scale_fill_manual(values = wes_palette("Cavalcanti1")))

ggsave(diet_area, filename = "diet_area.png",

height = 5, width = 8)

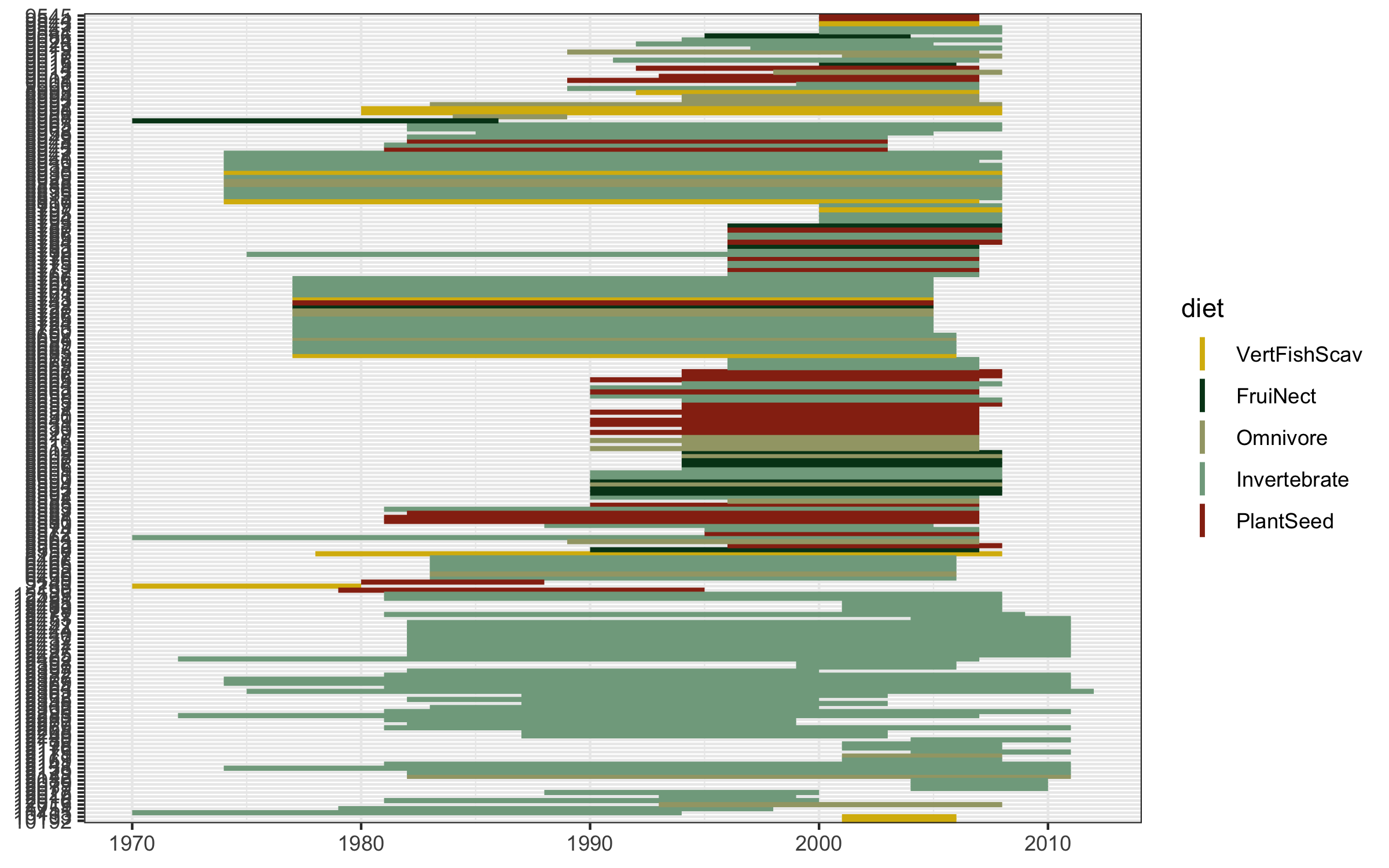

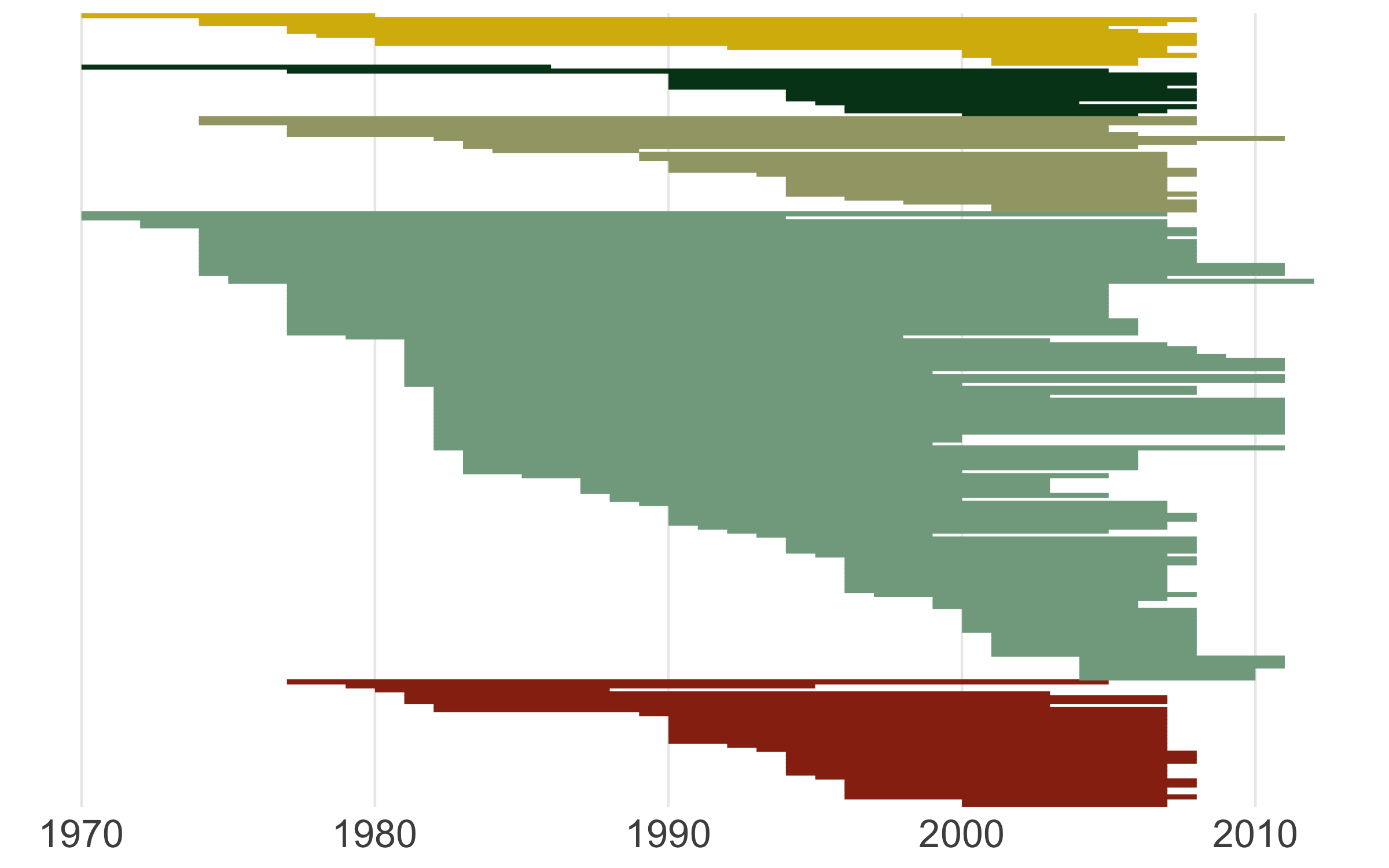

We’ve covered spatial representation of the data (our map), as well as the kinds of species (the diet figures), now we can cover another dimention - time! We can make a timeline of the individual studies to see what time periods are best represented.

# Timeline

# Making the id variable a factor

# otherwise R thinks its a number

bird_models_traits$id <- as.factor(as.character(bird_models_traits$id))

(timeline_aus <- ggplot() +

geom_linerange(data = bird_models_traits, aes(ymin = minyear, ymax = maxyear,

colour = diet,

x = id),

size = 1) +

scale_colour_manual(values = wes_palette("Cavalcanti1")) +

labs(x = NULL, y = NULL) +

theme_bw() +

coord_flip())

Well this looks untidy! The values are not sorted properly and it looks like a mess, but that happens often when making figures, part of the figure beautification journey. We can fix the graph with the code below.

# Create a sorting variable

bird_models_traits$sort <- bird_models_traits$diet

bird_models_traits$sort <- factor(bird_models_traits$sort, levels = c("VertFishScav",

"FruiNect",

"Omnivore",

"Invertebrate",

"PlantSeed"),

labels = c(1, 2, 3, 4, 5))

bird_models_traits$sort <- paste0(bird_models_traits$sort, bird_models_traits$minyear)

bird_models_traits$sort <- as.numeric(as.character(bird_models_traits$sort))

This sorting variable will help us arrange the studies first by species’ diet, then by when each study started.

(timeline_aus <- ggplot() +

geom_linerange(data = bird_models_traits, aes(ymin = minyear, ymax = maxyear,

colour = diet,

x = fct_reorder(id, desc(sort))),

size = 1) +

scale_colour_manual(values = wes_palette("Cavalcanti1")) +

labs(x = NULL, y = NULL) +

theme_bw() +

coord_flip() +

guides(colour = F) +

theme(panel.grid.minor = element_blank(),

panel.grid.major.y = element_blank(),

panel.grid.major.x = element_line(),

axis.ticks = element_blank(),

legend.position = "bottom",

panel.border = element_blank(),

legend.title = element_blank(),

axis.title.y = element_blank(),

axis.text.y = element_blank(),

axis.ticks.y = element_blank(),

plot.title = element_text(size = 20, vjust = 1, hjust = 0),

axis.text = element_text(size = 16),

axis.title = element_text(size = 20)))

ggsave(timeline_aus, filename = "timeline.png",

height = 5, width = 8)

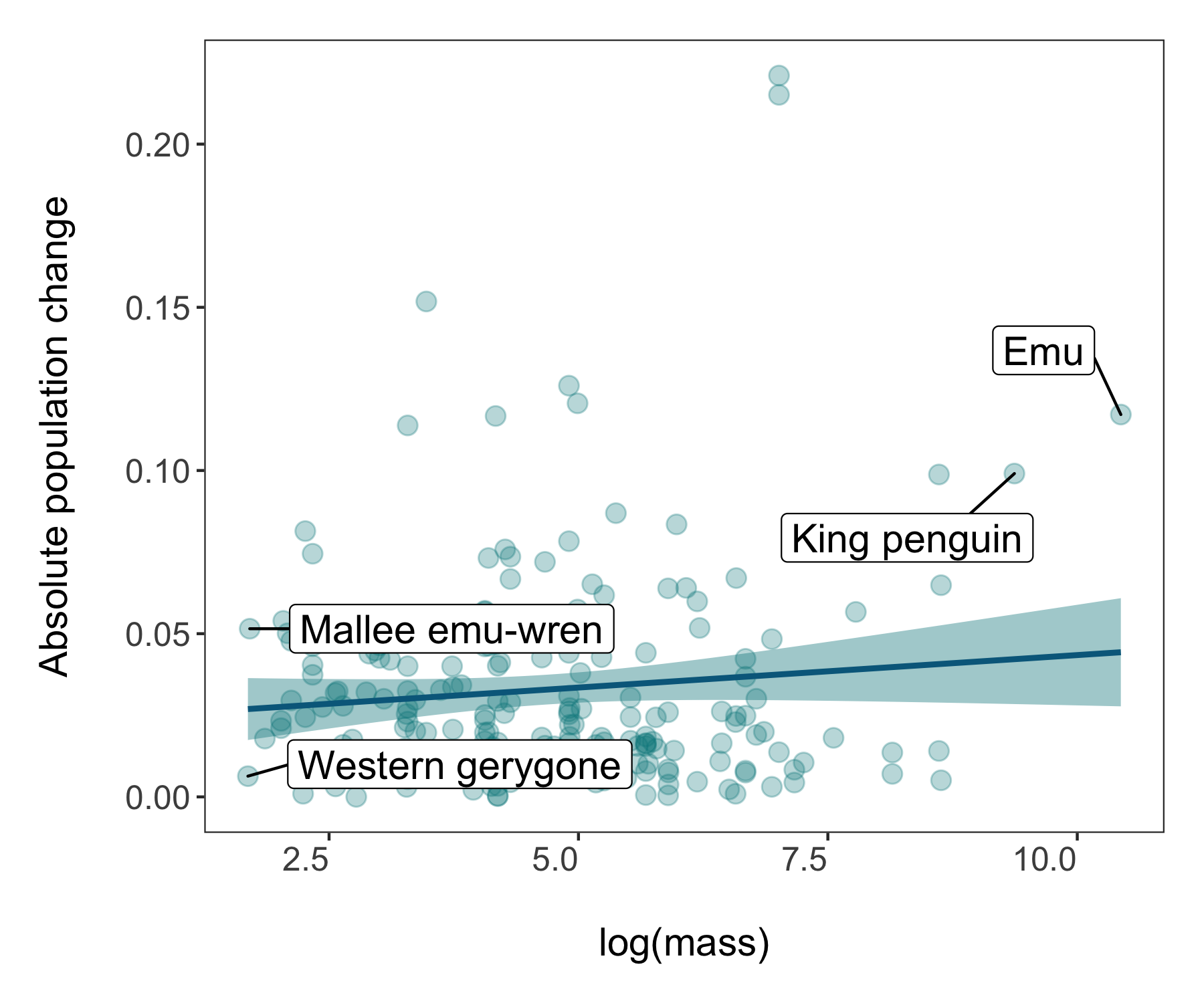

For our final figure using our combined dataset of population trends and species’ traits, we will make a figure classic - the scatterplot. Body mass can sometimes be a good predictor of how population trends and extinction risk vary, so let’s find out if that’s true for the temporal changes in abundance across monitored populations of Australian birds.

# Combining the datasets

mass <- bird_traits %>% dplyr::select(species.name, BodyMass.Value) %>%

rename(mass = BodyMass.Value)

bird_models_mass <- left_join(aus_models, mass, by = "species.name") %>%

drop_na(mass)

head(bird_models_mass)

Now we’re ready to unwrap the data present (or if you’ve scrolled down, I guess it’s already unwrapped…). Whenever we are working with many data points, it can also be useful to “put a face (or a species) to the points”. For example, we can label some of the species at the extreme ends of the body mass spectrum.

(trends_mass <- ggplot(bird_models_mass, aes(x = log(mass), y = abs(estimate))) +

geom_point() +

geom_smooth(method = "lm") +

theme_clean() +

labs(x = "\nlog(mass)", y = "Absolute population change\n"))

# A more beautiful and clear version

(trends_mass <- ggplot(bird_models_mass, aes(x = log(mass), y = abs(estimate))) +

geom_point(colour = "turquoise4", size = 3, alpha = 0.3) +

geom_smooth(method = "lm", colour = "deepskyblue4", fill = "turquoise4") +

geom_label_repel(data = subset(bird_models_mass, log(mass) > 9),

aes(x = log(mass), y = abs(estimate),

label = common.name),

box.padding = 1, size = 5, nudge_x = 1,

# We are specifying the size of the labels and nudging the points so that they

# don't hide data points, along the x axis we are nudging by one

min.segment.length = 0, inherit.aes = FALSE) +

geom_label_repel(data = subset(bird_models_mass, log(mass) < 1.8),

aes(x = log(mass), y = abs(estimate),

label = common.name),

box.padding = 1, size = 5, nudge_x = 1,

min.segment.length = 0, inherit.aes = FALSE) +

theme_clean() +

labs(x = "\nlog(mass)", y = "Absolute population change\n"))

ggsave(trends_mass, filename = "trends_mass.png",

height = 5, width = 6)

4. Download occurrence data through R

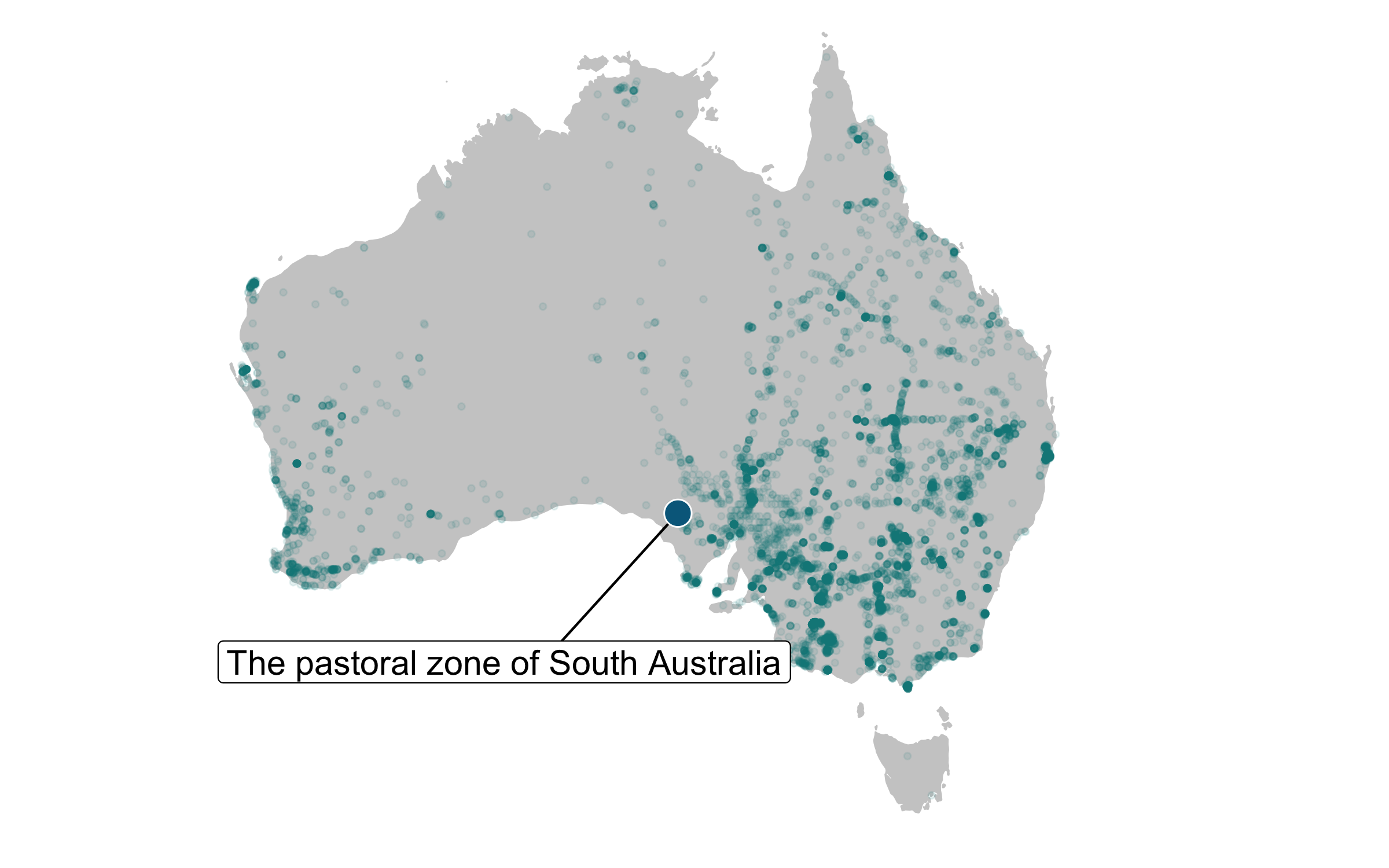

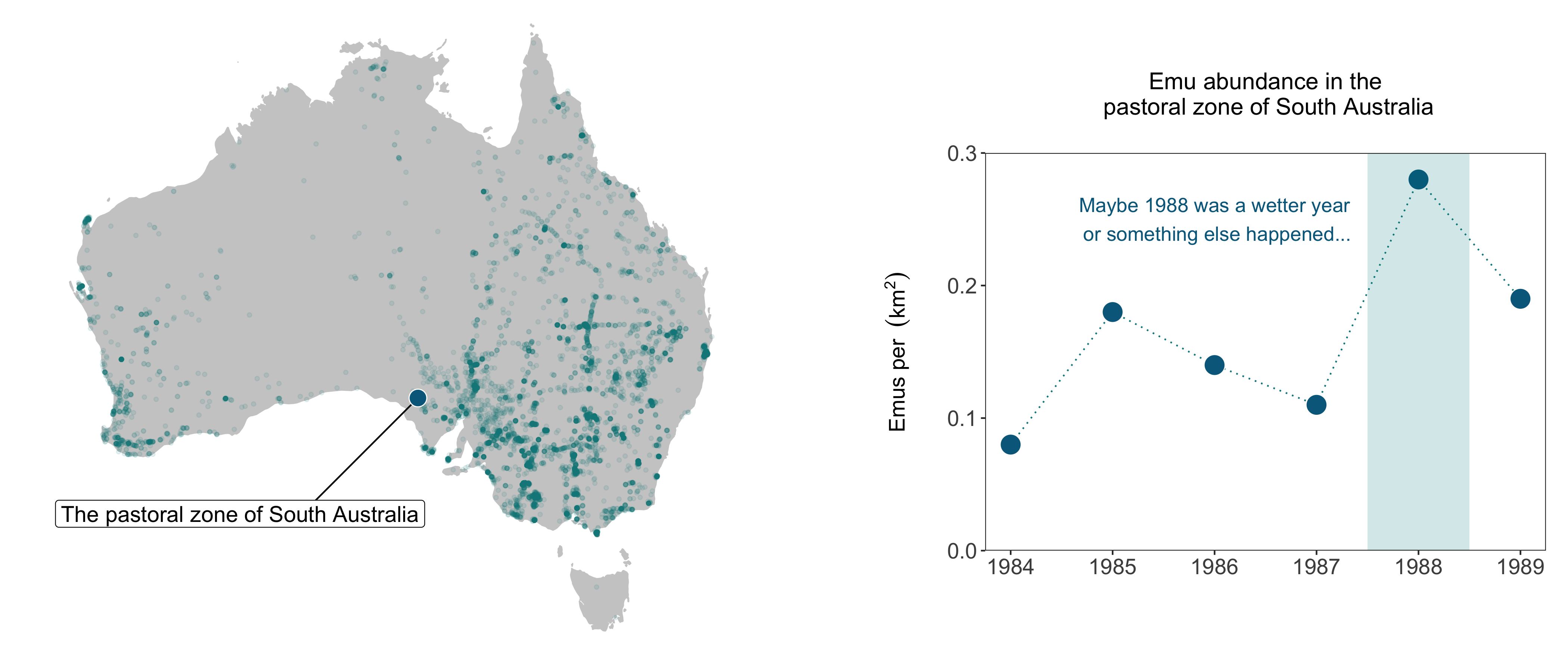

In this part of the tutorial, we will focus on one particular species, the emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae), where it has been recorded around the world, and where its populations are being monitored. We will use occurrence data from the Global Biodiversity Information Facility which we will download in R using the rgbif package.

# Even more data synthesis - adding in occurrence data

# and comparing it across where emus are monitored

# Let's see how many emu populations are included in the Living Planet Database

emu <- bird_pops %>% filter(common.name == "Emu") # just one!

But where do emus occur and where in the range is this one monitored population? We can find out by donwloading occurrence records for the emu from GBIF using the rgbif package.

# Download species occurrence records from the Global Biodiversity Information Facility

# *** rgbif package and the occ_search() function ***

# You can increase or decrease the limit to get more records - 10000 takes a couple of minutes

emu_locations <- occ_search(scientificName = "Dromaius novaehollandiae", limit = 10000,

hasCoordinate = TRUE, return = "data") %>%

# Simplify occurrence data frame

dplyr::select(key, name, decimalLongitude,

decimalLatitude, year,

individualCount, country)

Whenever working with any data, but especially occurrence data, we should check that they make sense and are valid and appropriate coordinates for the specific species. The CoordinateCleaner package is an awesome resource for working with occurrence data - you can check out the methods paper for it here.

# We can check the validity of the coordinates using the CoordinateCleaner package

emu_locations_test <- clean_coordinates(emu_locations, lon = "decimalLongitude", lat = "decimalLatitude",

species = "name", tests = c("outliers", "zeros"),

outliers_method = "distance", outliers_td = 5000)

# No records were flagged

Even though the tests didn’t flag up any records, we should still check if these data are fit for our purposes. In our case, we want to focus on emu occurrences in the wild, which happens only in Australia.

# We do want to focus on just Australia though, as that's the native range

summary(as.factor(emu_locations$country))

# Thus e.g. no German emus

emu_locations <- emu_locations %>% filter(country == "Australia")

We also want to plot the location of the emu population that’s part of the database we are working with.

# Getting the data for the one monitored emu population

emu_long <- bird_pops_long %>% filter(common.name == "Emu") %>%

drop_na(pop)

Now we are ready to combine them in one map and we can use the ggrepel package to make a nice label (rounded edges and all!) for the location of the monitored population.

(emu_map <- ggplot() +

geom_map(map = australia, data = australia,

aes(long, lat, map_id = region),

color = "gray80", fill = "gray80", size = 0.3) +

coord_proj(paste0("+proj=merc"), ylim = c(-9, -45)) +

theme_map() +

geom_point(data = emu_locations,

aes(x = decimalLongitude, y = decimalLatitude),

alpha = 0.1, size = 1, colour = "turquoise4") +

geom_label_repel(data = emu_long[1,],

aes(x = decimal.longitude, y = decimal.latitude,

label = location.of.population),

box.padding = 1, size = 5, nudge_x = -30,

nudge_y = -6,

min.segment.length = 0, inherit.aes = FALSE) +

geom_point(data = emu_long[1,],

aes(x = decimal.longitude, y = decimal.latitude),

size = 5, fill = "deepskyblue4",

shape = 21, colour = "white") +

theme(legend.position = "bottom",

legend.title = element_text(size = 16),

legend.text = element_text(size = 10),

legend.justification = "top"))

ggsave(emu_map, filename = "emu_map.png",

height = 5, width = 8)

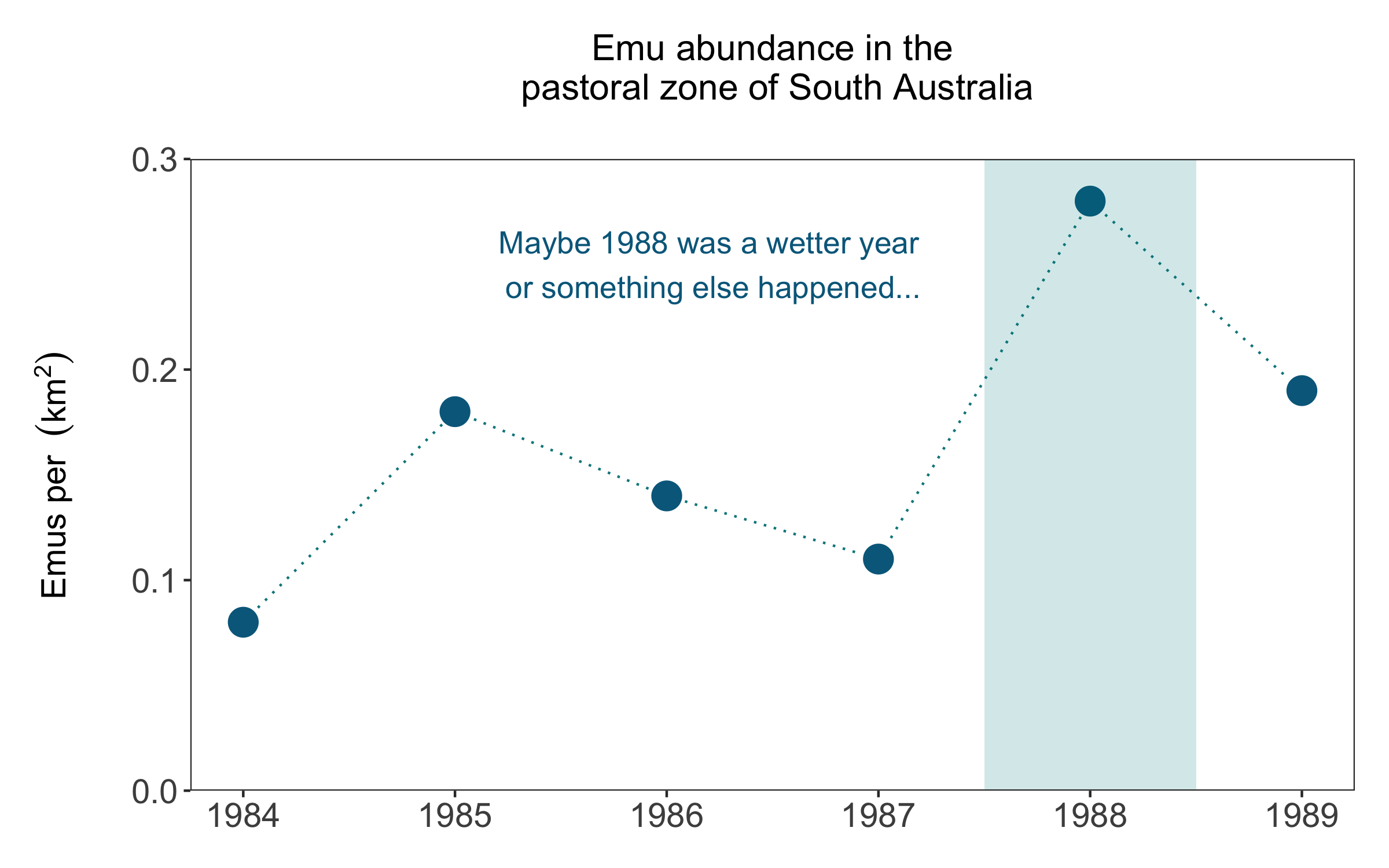

Finally, we can also make a line graph that shows the raw abundance estimates over time for the emu population in South Australia - that’d look nice next to the map! Like we’ve all the previous figures, you can compare between the quick figure and the more customised one.

(emu_trend <- ggplot(emu_long, aes(x = year, y = pop)) +

geom_line() +

geom_point())

(emu_trend <- ggplot(emu_long, aes(x = year, y = pop)) +

geom_line(linetype = "dotted", colour = "turquoise4") +

geom_point(size = 6, colour = "white", fill = "deepskyblue4",

shape = 21) +

geom_rect(aes(xmin = 1987.5, xmax = 1988.5, ymin = 0, ymax = 0.3),

fill = "turquoise4", alpha = 0.03) +

annotate("text", x = 1986.2, y = 0.25, colour = "deepskyblue4",

label = "Maybe 1988 was a wetter year\n or something else happened...",

size = 4.5) +

scale_y_continuous(limits = c(0, 0.3), expand = expand_scale(mult = c(0, 0)),

breaks = c(0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3)) +

labs(x = NULL, y = bquote(atop('Emus per ' ~ (km^2), ' ')),

title = "Emu abundance in the\n pastoral zone of South Australia\n") +

theme_clean())

ggsave(emu_trend, filename = "emu_trend.png",

height = 5, width = 8)

5. Create beautiful and informative figure panels

We’ve made lots of figures now, and in line with the general theme of synthesis, we can make a few panels that combine the different figures. We’ll use the gridExtra package for the panels, and one useful feature is that we can customise the ratios between the areas the different plots take - the default is 1:1, but we might not always want that.

# Panels ----

# Create panel of all graphs

# Makes a panel of the map and occurrence plot and specifies the ratio

# i.e., we want the map to be wider than the other plots

emu_panel <- grid.arrange(emu_map, emu_trend, ncol = 2)

# suppressWarnings() suppresses warnings in the ggplot call here

# (the warning messages about the map projection)

emu_panel <- suppressWarnings(grid.arrange(emu_map, emu_trend,

ncol = 2, widths = c(1.2, 0.8)))

Sometimes figures are fine as we had originally made them when they are presented on their own, but they need a bit of customisation when we include them in a panel. For example, we don’t need the line graph to be so tall, so we can artificially “squish” it a bit by adding in a couple of blank lines as a plot title. Or you can add a real title if you wish.

(emu_trend <- ggplot(emu_long, aes(x = year, y = pop)) +

geom_line(linetype = "dotted", colour = "turquoise4") +

geom_point(size = 6, colour = "white", fill = "deepskyblue4",

shape = 21) +

geom_rect(aes(xmin = 1987.5, xmax = 1988.5, ymin = 0, ymax = 0.3),

fill = "turquoise4", alpha = 0.03) +

annotate("text", x = 1986, y = 0.25, colour = "deepskyblue4",

label = "Maybe 1988 was a wetter year\n or something else happened...",

size = 4.5) +

scale_y_continuous(limits = c(0, 0.3), expand = expand_scale(mult = c(0, 0)),

breaks = c(0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3)) +

labs(x = "\n\n", y = bquote(atop('Emus per ' ~ (km^2), ' ')),

title = "\n\nEmu abundance in the\n pastoral zone of South Australia\n") +

theme_clean())

emu_panel <- suppressWarnings(grid.arrange(emu_map, emu_trend,

ncol = 2, widths = c(1.1, 0.9)))

ggsave(emu_panel, filename = "emu_panel.png", height = 6, width = 14)

As a final panel, we can have a go at combining more figures and varying the layout a bit. Check out how the panel dimensions change as you run through the various options of the code chunks.

# Map on top, two panels below

diet_panel <- suppressWarnings(grid.arrange(timeline_aus,

trends_diet, ncol = 2))

diet_panel_map <- suppressWarnings(grid.arrange(map, diet_panel, nrow = 2))

# The equal split might not be the best style for this panel

# change the ratio

diet_panel_map <- suppressWarnings(grid.arrange(map, diet_panel, nrow = 2, heights = c(1.3, 0.7)))

Looks okay, but there are still a few spacing issues we can solve. An easy, slightly cheating-style, way to sort out the spacing is by adding blank lines above and below graphs (in the graph title and x axis label).

(timeline_aus <- ggplot() +

geom_linerange(data = bird_models_traits, aes(ymin = minyear, ymax = maxyear,

colour = diet,

x = fct_reorder(id, desc(sort))),

size = 1) +

scale_colour_manual(values = wes_palette("Cavalcanti1")) +

labs(x = NULL, y = "\n") +

theme_clean() +

coord_flip() +

guides(colour = F) +

theme(panel.grid.minor = element_blank(),

panel.grid.major.y = element_blank(),

panel.grid.major.x = element_line(),

axis.ticks = element_blank(),

legend.position = "bottom",

panel.border = element_blank(),

legend.title = element_blank(),

axis.text.y = element_blank(),

axis.ticks.y = element_blank(),

plot.title = element_text(size = 20, vjust = 1, hjust = 0),

axis.text = element_text(size = 16),

axis.title = element_text(size = 20)))

(trends_diet <- ggplot() +

geom_jitter(data = bird_models_traits, aes(x = diet, y = estimate,

colour = diet),

size = 3, alpha = 0.3, width = 0.2) +

geom_segment(data = diet_means,aes(x = diet, xend = diet,

y = mean(bird_models_traits$estimate),

yend = mean_trend),

size = 0.8) +

geom_point(data = diet_means, aes(x = diet, y = mean_trend,

fill = diet), size = 5,

colour = "grey30", shape = 21) +

geom_hline(yintercept = mean(bird_models_traits$estimate),

size = 0.8, colour = "grey30") +

geom_hline(yintercept = 0, linetype = "dotted", colour = "grey30") +

coord_flip() +

theme_minimal() +

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(size = 14),

axis.text.y = element_text(size = 14),

axis.title.x = element_text(size = 14, face = "plain"),

axis.title.y = element_text(size = 14, face = "plain"),

plot.margin = unit(c(0.5, 0.5, 0.5, 0.5), units = , "cm"),

plot.title = element_text(size = 15, vjust = 1, hjust = 0.5),

legend.text = element_text(size = 12, face = "italic"),

legend.title = element_blank(),

legend.position = c(0.5, 0.8)) +

scale_colour_manual(values = wes_palette("Cavalcanti1")) +

scale_fill_manual(values = wes_palette("Cavalcanti1")) +

scale_y_continuous(limits = c(-0.23, 0.23),

breaks = c(-0.2, -0.1, 0, 0.1, 0.2),

labels = c("-0.2", "-0.1", "0", "0.1", "0.2")) +

scale_x_discrete(labels = c("Carnivore", "Fruigivore", "Omnivore", "Insectivore", "Herbivore")) +

labs(x = NULL, y = "\nPopulation trend") +

guides(colour = FALSE, fill = FALSE))

diet_panel <- suppressWarnings(grid.arrange(timeline_aus,

trends_diet, ncol = 2))

diet_panel_map <- suppressWarnings(grid.arrange(map, diet_panel, nrow = 2, heights = c(1.3, 0.7)))

ggsave(diet_panel_map, filename = "diet_panel.png", height = 9, width = 10)

Challenges

Take what you have learned about pipes and make a map of the five most well-sampled bird populations in the LPD database (the ones with the most replicate populations) and colour code the points by the population trend (derived from the models we did) and the size by the duration of the time series. Use another projection for the map - the default is Mercator, but that’s not the best way to represent the world. Hint - you can still use ggplot2 - look up the ggalt package.

Pick a country and species of your choice. Download the GBIF records for that species from your selected country (or you can do the world if you don’t mind waiting a few more minutes for the GBIF data to download). Plot where the species occurs. Then, add the locations of the Living Planet Database populations of the same species - do we have long-term records from the whole range of the species? Where are the gaps? From what time period are the species occurrence records? Can you colour code the points by whether they are in the first half of the period or the second? You can have a go at highlighting certain records using the gghighlight package (you can find out more about it on its GitHub repo).

Can you think of any data you can combine with some of the data from the tutorial in a meaningful way? If looking at the graphs from the tutorial has spurred further questions in your head, have a go at integrating the data from the tutorial with a new dataset and create a panel combining at least two figures.

Extra resources

To learn more about the power of pipes check out the tidyverse website and the R for Data Science book.

To learn more about purrr check out the tidyverse website and the R for Data Science book.

For more information on using functions, see the R for Data Science book chapter here.

To learn more about the tidyverse in general, check out Charlotte Wickham’s slides here.